Dyslexia is a language-based disorder. But so is Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). Are they the same thing?

Tricky question – and one that comes up a lot in my clinic when I’m working with struggling school-aged students.

Luckily, much bigger brains than mine – including Professors Suzanne Adlof and Tiffany Hogan – have been looking at this question. This line of research has helped inform our approach to assessing and treating children with dyslexia, DLD, and both dyslexia and DLD.

We thought it would be useful to summarise some of our key takeaways to help others who may be thinking about the relationship between dyslexia and DLD.

1. But first, some difficult definitions

The definition of dyslexia is controversial. Despite attempts to reach consensus, there is also no universally accepted definition of DLD.

Definitional issues get in the way of research, knowledge translation and advocacy. Without minimising the academic importance of such debates, parents, front line educators and health professionals, and others working with children with dyslexia and/or DLD need to understand the recent research so they can seek/deliver the best outcomes. So, for this article only:

“dyslexia” means:

- severe difficulty learning how to read; despite

- normal vision; and

- adequate reading instruction; and

- adequate cognitive abilities (i.e. no intellectual disability) (e.g. Lyon et al., 2003); and

“DLD” means an unexpected deficit in language abilities despite adequate environmental stimulation and cognitive abilities with no neurological impairments (e.g. Bishop et al., 2017).

2. Parallels

Clearly, there are some parallels. Both dyslexia and DLD:

- are language-based disorders;

- are deficits that are “unexpected” given the absence of intellectual disabilities or other medical explanations; and

- require the child to have received adequate environmental stimulation: appropriate reading instruction for dyslexia, and adequate human language interactions for DLD.

3. So what’s the difference?

(a) Phonological deficits vs. multi-dimensional language deficits:

In dyslexia, the principal deficit is word reading. Most definitions of dyslexia include marked difficulties with word reading, decoding, and spelling. Many descriptions focus on phonological deficits as a core feature of dyslexia (e.g. Moats, 2008).

Phonology is the system of contrastive relationships among the speech sounds that constitute the fundamental components of a language. Phonological deficits impact the specificity at which sounds are stored and recalled in words, as well as the reader’s ability to manipulate sounds in words and connect sounds to letters to read words. Lots of evidence shows that children with dyslexia, on average, perform poorly on tasks that involve phonology, including phonological awareness, word and nonword repetition, and word retrieval (e.g. Vellutino, et al., 2004).

In DLD, children may have language deficits across multiple dimensions of language. These can include phonology. But they can also affect vocabulary, semantic knowledge, morphology, syntax, and the social use of language: the so-called content, form and use of language.

(b) Biologically primary v. secondary knowledge

Oral language is biologically primary knowledge – humans as a species have a natural instinct for it. Reading words is biologically secondary – or unnatural. In evolutionary terms, decoding written words is a recent development and everyone has learn how to do it. (Incidentally, that’s one reason why many definitions of dyslexia (controversially) exclude reading problems caused by poor instruction. Otherwise, everyone who was illiterate would be dyslexic, which is not the case.)

4. But don’t forget the Simple View of Reading!

There is an important – if confusing – overlap of concepts when it comes to reading. Being a good reader means more than only reading the words on the page – you need to understand what you are reading, too. Reading comprehension is the product of accurate and efficient word reading and language comprehension. So when assessing people with reading problems, education and health professionals need to look at both decoding skills (which may be relevant to a diagnosis of reading difficulties or dyslexia), as well as general language comprehension skills (which may be relevant to a diagnosis of DLD).

Many reading comprehension skills are based on biologically primary oral language or other knowledge. Oral language comprehension skills, phonological awareness, vocabulary and naming skills, theory of mind, knowledge of human relationships, knowledge of biology (notably animals and plants), and physical environments – as well as background knowledge about the world – contribute to helping kids understand what they read.

The key point is that good reading comprehension requires good decoding skills and good language comprehension skills; and that deficits in either (or both) can cause clinically significant reading problems. In other words, children with dyslexia and many children with DLD have reading problems. But reading problems can be caused by decoding problems, language comprehension problems or both – and it is essential to find out which deficits are contributing to a child’s difficulty reading so that you can plan the right intervention.

(You can read more about the so-called “Simple View of Reading” here. You can read more about biologically primary and secondary knowledge here.)

5. So, if dyslexia is a language based disorder, do all children with dyslexia have DLD? Will all children with DLD be dyslexic?

The short answer appears to be “no” and “no”. Although the science is not yet settled, DLD and dyslexia appear to be distinct disorders that can co-occur.

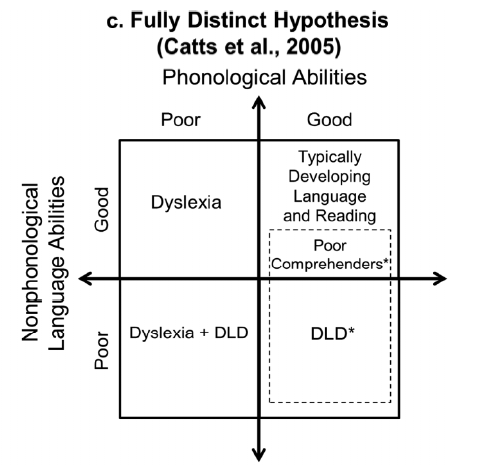

Catts et al., 2005, for example suggests that:

- the majority of children with DLD do not have dyslexia; and

- the majority of children with dyslexia do not have DLD; and

- phonological deficits are more closely related to dyslexia than DLD.

This research supports the so-called “fully distinct hypothesis”, which can be depicted as follows:

(Picture credit: Adlof & Hogan, 2018 – see full citation below)

Current evidence also suggests:

- dyslexia and DLD frequently co-occur, although no one knows exactly how often (different studies, with different designs, show a 17-71% co-occurrence!);

- some children with dyslexia who do not have DLD still present with relatively weak language skills compared with typically developing peers, e.g. with poorer vocabulary, sentence repetition, and syntax comprehension skills, that are still within the normal range (e.g. Bishop et al., 2009);

- some children with dyslexia present with normal or even above-average oral language skills (e.g. Alt et al., 2017; De Groot et al., 2015); and

- some children with dyslexia but normal oral language skills (i.e. no DLD) show poor word learning compared to typically developing children, especially when it comes to learning the phonology of new words (e.g. Alt et al., 2017).

6. What do we do with this research? Our clinical takeaways

This research has had – and continues to have – a big impact on our clinical practice. Our key takeaways are as follows:

- Everyone working in child literacy – parents, researchers, speech pathologists, teachers, educational psychologists, and students themselves – need to know that dyslexia and DLD are distinct but often co-occurring disorders.

- It is likely that at least half of the children identified with reading difficulties in schools will have co-occurring (but perhaps undiagnosed) DLD (e.g. G.M. McArthur et al., 2000).

- Many children with dyslexia who perform within normal limits on standardised language tests may still have significant (if sub-clinical) language difficulties that may warrant monitoring and accommodations.

- Students with dyslexia – regardless of whether they also have DLD – are at risk of slower language acquisition and slower growth of world knowledge across their lifetime because of reduced reading experience – the so-called Matthew Effect. In addition to high quality, evidence-based reading instruction, these students may benefit from compensatory techniques that build their exposure to great books/texts and increase knowledge about the world other than through print, e.g. through audiobooks or video recordings of school texts (e.g. Milani et al., 2010).

- When assessing school-aged children with reading difficulties, it is essential that the assessment battery include both reading and oral language assessment tasks including tests of phonology, orthography (spelling), morphology, semantics, vocabulary, syntax and discourse processing.

- Regardless of the label (or labels), intervention needs to be tailored to target each child’s strengths and weaknesses across all domains of language, in part because they all impact reading comprehension.

- Teachers, speech pathologists, psychologists, reading specialists and special educators need to collaborate to help support students with multiple needs. We also need to educate each other – to share our knowledge and avoid inconsistent jargon – to address reading and oral language issues for students under our care.

Principal source: Adlof, S. M., and Hogan, T.P. (2018). Understanding Dyslexia in the Context of Developmental Language Disorders, Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49, 762-773.

For more information about DLD, see, follow and support the wonderful work of Raising Awareness of Developmental Language Disorder.

Related articles:

- Is your child struggling to read? Here’s what works

- Developmental Language Disorder: a free guide for families

- “I don’t understand what I’m reading!” – reading comprehension problems (and what to do about them)

- For struggling school kids, what’s the difference between seeing a speech pathologist and a tutor?

- Kick-start your child’s reading with speech sound knowledge (phonological awareness)

- How to find out if your child has a reading problem (and how to choose the right treatment approach)

- Too many children can’t read. We know what to do. But how should we do it?

- Are reading comprehension problems caused by oral language deficits?

Image: https://tinyurl.com/y4wf5de6

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.