We work with many children who have unclear speech. For some families, speech therapy can be mysterious, confusing, tedious, or even intimidating. It shouldn’t be any of those things.

In this article, we will explain what we do and why we do it. We’re going to answer some questions we get asked a lot. We’re going to try to avoid (or at least explain) jargon and acronyms that plague the topic. Where possible, we’ll link to some other articles that address some of the points we cover in more depth.

Speech sound disorders – when to be concerned

Most children learn to speak without any help. But some experience significant delays in learning to use speech sounds correctly in speech. We call these delays ‘speech sound disorders’.

Learning to speak like an adult takes time; and all young children make at least some speech errors. When should you be concerned?

Unfamiliar adults should be able to understand about 80% of a typically developing 3-year old child’s speech. By four years of age, children should be fully intelligible to unfamiliar adults (Gordon-Brannan & Weiss, 2006).

Here are some rules of thumb. If:

- your child is 3 years old (or older) and adults can’t understand most of what he or she says; or

- your child’s speech is getting negative attention from peers or others, e.g. teasing or bullying at preschool; or

- your child is 4 years old and isn’t 100% intelligible to unfamiliar adults; or

- an early educator or carer working with your child is concerned about your child’s communication skills; or

- you are concerned for any other reason about your child’s communication skills,

you should touch base with your local speech pathologist for a chat.

Aren’t speech delays temporary? Why does it matter?

About 75% of children with speech sound disorders correct their speech by the age of 6 years. Of the remaining 25%, most resolve by the age of 9 years. A small percentage continue to have residual problems, often with sounds like /r/, /s/ and the ‘th’ sounds (e.g. in ‘thing’, and ‘this’) (Shriberg et al., 1997; Kamhi, 2006).

So why not just wait?

The evidence is clear: children with speech sound disorders are at a higher risk for problems down the track. Systematic reviews have shown that children with speech sound disorders are at greater risk than typically developing children when it comes to:

- learning to read;

- learning to write;

- focusing their attention and thinking;

- communicating with others;

- caring for themselves independently;

- relating to people in authority (e.g. teachers, older children, managers);

- informal social relationships with friends and peers;

- relationships with their parents;

- relationships with their brothers and sisters;

- school readiness and academic success; and

- getting and keeping a job.

(e.g. McCormack et al. 2009.)

As we explain here, a child’s school readiness is:

- predictive of academic outcomes (e.g. Snow, 2006); and

- a strong indicator of ongoing and future success (e.g. Prior et al., 1993).

As a speech pathologist with a special interest in school-aged language and reading, I am particularly concerned when I meet a child about to start school with unclear speech, difficulty distinguishing speech sounds, and difficulties expressing their thoughts and feelings in sentences.

Does evidence-based speech therapy work?

Yes: this has been proven by systematic reviews of peer-reviewed research evidence (e.g. Law et al., 2004). Similarly, evidence from a comprehensive 2011 narrative review suggests that it is better for children who have phonological impairments to receive intervention than no intervention at all (Baker & McLeod, 2011).

Children have their best chance of fulfilling their potential if they are provided with effective and efficient treatment before starting school (Baker & McLeod, 2011; Beitchman et al., 2001, Nathan et al., 2004). But it is never too late to get help with your speech, and we work with many adults with speech sound issues.

Are there different kinds of Speech Sound Disorders?

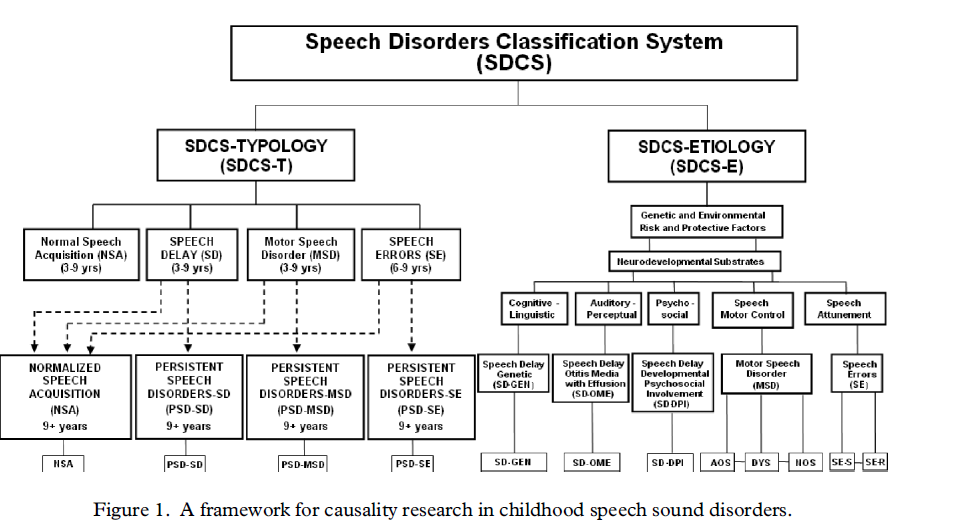

Yes. Some researchers have tried to classify them. For example, the Speech Sound Disorder Classification System looks like this:

(Shriberg et al., 2010).

This classification system is very complicated, and not everyone agrees with it. I like it in concept, but find it hard to apply in practice. Instead, in our clinic, we tend to group speech sound disorders into three broad categories that are not mutually exclusive: language-based, articulation-based, and motor speech-based speech disorders.

Language-based speech disorders:

- The most common kind of speech sound disorder is something called a ‘phonological impairment’ (Baker & McLeod, 2011). This sounds scary, but ‘phonology’ is simply the science of speech sounds; and ‘impairment’ just means there is a delay, difficulty or problem with speech.

- The important thing to know is that this type of disorder is a language-based impairment. It affects more boys that girls, and often (but not always) runs in families. (You can read more about risk factors for language disorders here and here.)

- Children with phonological problems, tend to have patterns of errors called ‘phonological processes‘ e.g. they may leave out weak syllables, sounds in consonant clusters or the final sounds in words, or they may switch sounds (like /w/ for /r/, or /d/ for voiced ‘th’).

- Most of our clients who have unclear speech have this kind of speech sound disorder.

Articulation-based speech disorders:

- Sometimes, children simply don’t know how to produce a speech sound correctly.

- For example, some children with interdental lisps have no problems hearing the difference between /s/ and unvoiced ‘th’. They know that they are saying /s/ incorrectly. But they have not yet learned to put their tongue tip in the right place.

Motor-based speech disorders:

- Far less often, we work with children with motor speech disorders.

- They include rare disorders like childhood apraxia of speech (problems planning or programming speech movements) and dysarthrias (poor articulation caused by damage to the nervous system).

- Every now and then, children present with speech motor delays or difficulties that are neither childhood apraxia of speech or dysarthria.

Classifying a given client’s speech sound disorder is not always clear cut. Children don’t tend to fit into neat categories. For example:

- some children make errors that are both language-based and articulation based. For example, a child may not be able to hear the difference between /s/, ‘th’ and /f/ (a language-based issue), and may also not know how to produce ‘th’ with the tongue tip between their teeth (an articulation issue); and

- some children present with lots of phonological error patterns (a language-based issue) but also have visible difficulties coordinating their tongue, teeth, lips and voice to make speech sounds correctly in words with three or more syllables or in connected speech (articulation and motor speech issues).

You have to look at the child in front of you and work out what’s going on with their speech.

What do we assess and how do we assess speech?

Our speech assessments are designed to help us figure out:

- whether a client has a speech sound disorder; and

- if so, whether language-based, articulation, and/or motor speech issues are contributing to the difficulties.

To get this information, we:

- interview the family and ask them lots of questions before their first appointment, particularly to identify risk factors, get an idea of the child’s personality and interests, and understand what matters most to the family;

- observe the child doing something natural, like play;

- administer standardised speech tests, like the Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology, to obtain single word and short connected speech samples, or the Nonword Repetition Test to test – you guessed it – nonword repetition skills;

- assess the child’s ability to produce polysyllabic words. We explain why we do this here;

- elicit language samples, usually through a combination of conversation, picture descriptions, and narrative retelling tasks;

- assess (or at least screen) oral language development, so we can evaluate whether expressive language issues, e.g. with vocabulary, semantics, morphology, syntax and use may also be present (as they frequently are);

- conduct an oromotor examination focused on speech coordination tasks, to assess whether any structural issues (e.g. cleft palate, muscle weaknesses) might be contributing to speech difficulties, and to assess how the child plans and executes speech tasks, including syllable repetitions and sequences; and

- assess phonological awareness for preschoolers (particularly if they are soon to start school), focusing on speech sound blending and segmenting skills, and letter-sound links for reasons explained here.

Depending on the results, we might need to do other tests and assessment tasks, e.g. if we are concerned about whether a client might have childhood apraxia of speech.

So what, exactly, do we do in therapy?

This is a question we spend a lot of time asking ourselves. It’s a question we expect to keep asking ourselves as more research is published and as we become better at what we do.

As health professionals, we are committed to evidence based-practice. This means we need to consider and then integrate three things:

- the best peer-reviewed research;

- our clinical expertise; and

- our clients’ (and their families’) values and goals (Sackett et al., 2000).

(1) The best research

It’s hard to find and apply the best research for clinical use. Key challenges include:

- the number of studies. People have been working on therapies for speech sound disorders for over 100 years; and there are at least 135 published studies (Baker & McLeod, 2011). More are being published every year. For example, just before I started writing this article, I read a new randomised control trial of an intervention for children with motor speech difficulties (Namasivayam et al., 2020). It can be hard to keep up!

- the number of different treatments. There are at least 46 (Baker & McLeod, 2011);

- the number of different treatments goals. There are at least seven different ways to choose what to work on (Baker & McLeod, 2011);

- the mixed quality of studies. Not all studies are of equal value. Some treatments are supported by high quality, replicated studies (e.g. randomised controlled trials). Others are more prone to bias, like case reports and book chapters written by people who developed the therapy;

- poor clarity of some studies. To implement a treatment, we need clear descriptions of the invention, including who it is for, what it involves, the elements of the intervention itself, including what we need to do in therapy, the materials we should use to do it, and information about treatment frequency and dose. Unfortunately, many intervention studies don’t give us enough detail to do the actual therapy. Some studies contain enough information to allow us to get the basic idea and trial it, but not enough procedural detail on the nuts and bolts of the therapy to know whether we are doing the treatment in the same way as the researchers. For example, the randomised study I read this morning contains almost no information about the treatment and how to do it. This is incredibly frustrating for speech pathologists in clinical practice who want to apply new research to help their clients;

- diversity of clients with speech sound disorders. Every child with a speech sound disorder is unique. Some have severe impairments, others only mild issues. Some have motor speech issues, others have language-based error patterns, still others have articulation issues, and yet others have elements of all three. For some clients, their only area of challenge is with speech sounds. Most of my speech clients have additional challenges, including language disorders, stuttering, voice disorders, ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorders, sleep disorders, behavioural and emotional difficulties, adenoid and tonsil issues, or hearing issues, just to name a few. It can be hard to know up-front which approach is likely to work with which client – especially when studies routinely screen out participants with more than one area of challenge; and

- few studies pit one treatment against another. With a few exceptions, there are not many studies showing that one phonological intervention is better than another.

Despite these difficulties, it is our job to do our best to translate new research on effective treatments into practice. Examples of evidence-based therapies we have been able to translate or adapt and use in our clinical practice include:

- the Complexity Approach for phonological impairments;

- the normative (or developmental) approach based on knowledge of typical consonant acquisition and ages at which phonological error patterns are typically eliminated.

- the Cycles Phonological Remediation Approach for children with severe phonological impairments;

- Minimal Pairs, Multiple Oppositions and other contrastive approaches, sometimes based on developmental sequences of sounds, and sometimes based on complexity principles;

- DTTC therapy for younger children with severe childhood apraxia of speech; and

- ReST treatment for older children with childhood apraxia of speech.

Sometimes, we’ve had to send staff off on expensive post-graduate training courses to learn therapies. But, increasingly, researchers are making their training materials freely available and accessible at any time, which is a huge help for busy clinicians. Two examples are ReST and DTTC – both treatments for childhood apraxia of speech.

(2) Clinical expertise – what do we do in speech therapy?

When I think about the multitude of phonological interventions, I’m reminded of a funny quote from the (now terribly dated) 1980s English comedy, ‘Allo ‘Allo:

“He was the man of a thousand faces – every one the same.”

With the experience of using several different approaches, common features and patterns emerge: elements that seem to work most of the time, regardless of which therapy approach we take.

Of course, many brighter minds than mine have observed the same thing. Noting that many therapy approaches seem to work, some researchers have questioned the importance of finding ‘the’ best treatment approach, and highlighted instead the importance of identifying the best therapy targets (e.g. Gierut, 2005). In other words, what is treated may be more important than how it is taught (e.g. Kamhi, 2006). But I think it goes further than just targets and approaches: beneath the surface, many therapies share more similarities than differences – especially when they are translated into practice.

What follows are some examples of therapy elements and practices that we have found help our clients to improve their outcomes in speech therapy, regardless of which approach we take. Some are consistent with principles of effective language therapy (e.g. Bayles, 2011; Gillam & Loeb 2010). Others are more consistent with principles of motor learning. Some are principles distilled by researchers thinking about how we move speech pathology practices forward (e.g. Kamhi, 2006; Rvachew, 2017; Baker et al., 2018). Others are just things we have found work for many families.

(a) General elements

- Engaged client and family. Motivated, focused clients tend to do better than disengaged or inattentive clients.

- Client as the focus. We start each session by explaining our goal and why it matters in language that the child can understand. We use visuals to explain what we are doing and why. We make the client the most important part of therapy: not family members, and certainly not ourselves!

- Informed families: Children with families who understand and support the therapy goals and the approach – including the importance of the core elements of the treatment – tend to do better in therapy than those who don’t. It’s our job to make sure our clients’ families make informed decisions about their child’s therapy.

- Families as therapy partners. Families who understand the importance of doing the work between sessions and feel confident to do it – understanding the whys, whats and hows of therapy – do better than families who feel removed from therapy.

- Regular sessions and attendance. It is not always possible to see a client multiple times a week. But we usually recommend an initial therapy block of at least weekly sessions to maintain our high dose of therapy and treatment momentum. Children who miss sessions frequently don’t tend to do as well as clients that attend regularly as scheduled.

- Structured and routine-based. Our speech therapy is highly structured, especially in the early weeks. We use visual timetables to outline the order of activities, with structured activities gradually opening up to more naturalistic play activities to promote conversation. We try to keep the flow of the sessions (including the order of tasks) constant, so we can turn therapy into a fast-flowing routine. Clients don’t need to guess what’s next.

- Clinic- and telehealth-based. This is both a strength and constraint of our therapy. Most of our work happens in small clinic rooms designed to remove distractions and to motivate clients to do the work. For remote clients (and for all clients during pandemics) we deliver therapy by telehealth.

- Challenging. We set ambitious goals for clients, especially if they are starting school soon. Sometimes, this means our therapy sessions are less fun than they could be (e.g. if we spent more time playing games or went for fewer repetitions). But we find that many of our clients thrive with our high expectations.

- Outcomes measured and shared: We measure changes in the percentage of consonants a child can say correctly. At a bare minimum, we want a 5% change (Thomas-Stonell et al., 2013) over a 3-6 month period – any less than that and we can’t be sure we are making a difference. I like to push for a 10-15% increase in percentage of consonants correct measured in a single word naming task – an ambitious goal that is not achieved by every client.

- Pragmatic approach to finding something that works: Research tells us that about 1/10 children do not improve meaningfully over 3-6 month treatment, even when the treatment is effective for others (Rvachew, 2017). We need to spot these children early, explain what’s happening to families, and try different approaches. In clinical practice, we have to be prepared to switch treatments if the one we recommended isn’t working for the particular child in front of us.

- Regular therapy breaks and discharge: If therapy blocks go on for too long, they can become unfocused and drift. Clients (and families, and speech pathologists) can lose motivation and perspective on what they are working on (and why). Therapy breaks can help keep things fresh. We are constantly impressed with gains made by clients during breaks in therapy. Obviously, when clients have met their goals, we discharge them.

(b) In the sessions

- Parent/carer in the room. Most clients seem to do better when the parent in the room while therapy is done. Apart from helping us to comply with our child safety procedures, this helps parents to understand what we are doing in therapy. It also provides an opportunity for us to model therapy for the parent so they can do the practice at home.

- Practice speech! We do not waste time doing non-speech motor exercises like tongue wiggling or blowing exercises because they don’t improve speech. If you want to get better at speech, you have to practice speaking. This can sometimes be tricky if you are working with a shy or anxious child (and especially if the child is selectively mute). But we have lots of tricks to encourage speech!

- Intense Dose: Repetition, repetition, repetition. Ideally, we go for 150-200 repetitions in a 45 minute session, especially when working with children with motor speech difficulties. Sometimes we get more repetitions, sometimes we get fewer. But when it comes to therapy dose, the research shows that more is often more! Introducing a sense of ‘urgency’ into speech therapy, e.g. through simple ‘races’, or other competitive or collaborative games, can help to ratchet up the repetitions while keeping the sessions engaging. We just have to take care to ensure that the reinforcement doesn’t take over the session, and that the activity doesn’t replace the goal.

- Words as targets: The entry level for speech and language development is babbled syllables and first words – not sounds on their own, or morphemes (Walley et al., 2003). For this reason, we use words in therapy. For some approaches, we start with simple vowel-consonant, consonant-vowel, consonant-vowel-consonant combinations (e.g. ‘it’, ‘car’ (with an Australian accent) and ‘bat’). For others, we focus on words containing complex clusters of consonants, e.g. ‘play’ or ‘splash’, and polysyllables like ‘helicopter’. But we don’t spend much time on sounds in isolation.

- Preference for real words: Particularly for children with language and speech disorders, we prefer to use real words. Where possible, we choose targets that are functional – I like to include verbs where possible. For very young children, I look for developmentally typical first words often with simple phonology. For older children, I use words taken from the General Service List-Spoken. Less often, we use non-words (e.g. in the ReST treatment for Childhood Apraxia of Speech).

- Pictures with words: We use pictures to help preliterate children to say the words. But we always include the written words as well to help young children increase their print awareness and older children to build letter-sound links, and phoneme blending and segmenting skills, which are related to reading development.

- Not too many examples of each target. Provided we get in enough total repetitions, we find that targeting as few as five words a session (say 40 times each) is often enough to get transfer to other words with the same target. We started this practice with Cycles, but now use it with other approaches, including Complexity and Minimal Pairs.

- Modified signal, less noise: modelling target words slowly (but without segmenting them into individual speech sounds), manipulating primary stress when presenting words in sentences, and using word order to highlight the target at the end of phrases all seem to help. We try to keep outside noise to a minimum (even if that means banishing the sibling to the reception play area).

- Auditory bombardment and discrimination tasks: starting out with our experience in Cycles, we have found that working on speech perception seems to improve speech production outcomes – although we know they are separate concepts, and we are not entirely sure why it helps. We know that many children with speech sound disorders have problems with speech perception. Recent research seems to support our clinical observations (e.g. Hearnshaw et al., 2019). Routinely, we use auditory bombardment and/or speech discrimination tasks to help children to tune into different speech sound targets, especially for children with phonological impairments.

- Distributed and interleaved practice; cyclical goal attack. We’ve found it is better for many clients if we take a cyclical approach to goal-setting. We don’t spend too long in therapy on one sound, but keep moving, circling back to targets that are yet to be acquired. This reduces frustration for everyone, and tends to promote greater overall gains.

- Targets: improving the child’s overall speech system is more important than any particular sound. We want our therapy to work (be effective). But we also want it to be efficient – for many children with severe speech sound disorders, we don’t have time to target sounds one at a time. We prefer approaches that seek to make system wide changes to the child’s speech, rather than just improving single sounds. We prefer to target error patterns, rather than individual errors. We use the Complexity Approach, Cycles and/or Multiple Oppositions most often to do this, and don’t tend to use traditional articulation therapy very often.

- Errors of omission before errors of substitution. We learned this one from Cycles, and from reading some of the research about the effects of speech sound disorders and early reading outcomes. If our goal to increase a child’s intelligibility (as it almost always is), we find the targeting error patterns where children leave out sounds in words gives us better results than targeting error patterns where the child switches one sound for another. For example, we’ve found that working on syllable deletion, initial and final consonant deletion, and cluster reduction increases many children’s overall intelligibility more than working on, say, gliding of /r/ to /w/ or simplification of ‘th’ to /f/. We also find that we can combine targets for children with severe difficulties, e.g. teaching children to produce /f/ at the end of words allows us to work on fricatives (hissy sounds) and final consonant deletion at the same time.

- Carrier phrases as a bridge to sentences and conversation. We’re big fans of using carrier phrases to practice target words in sentences, especially for children with speech and expressive syntax delays, and children with speech disorders who also stutter. Helping children to acquire simple subject verb object word order, and more complex sentences, e.g. containing because and if, helps you to work on multiple goals at once, even if you are focusing your direct treatment on speech sounds. Even with older school aged children, we frequently work on improving speech sounds while also working to improve their decoding skills, vocabulary, categories and other semantic knowledge, complex syntax, and social use of language, e.g. with sequencing, narrative tasks, conversation skills or other discourse level language tasks.

- Lots of feedback on accuracy, especially in the early stages of therapy.

- Reinforcement for correct responses (including self-corrections). Many speech therapies are based on behavioural science. While I’m ambivalent about the use of external reinforcement, it certainly has a role in reinforcing success and changing behaviour, and can be a big help to increase motivation and focus, especially when working with very young children. We find that praising children for noticing and ‘fixing up’ (correcting their own errors) has a positive effect, a practice we learned from Dr Caroline Bowen and her incredible website.

- Some children respond to complex targets. Others don’t. Children need some resilience to engage in therapy using the complexity approach. Some children do better by following a developmental sequence – targeting earlier developing, less complex sounds and error patterns so can get some success straight away. We also find that some children start out with developmental targets and, after success, are willing to have a go at more complex targets. Interestingly, we see transfer to other sounds both ways.

- Phonological awareness for preschoolers: For children getting ready for school, we include at least one phonological awareness target in therapy, usually working on letter-sound links, or blending or segmenting tasks. Again, we do this because these skills are important for later literacy development.

- Randomised practice: Once the child has achieved the target with simple words, I like to randomise exercises, mixing up activities at the word, phrase, sentence, verbal problem solving, and discourse levels, and adding in extra challenges like dual tasking. I do this with my nerdish collection of Dungeons & Dragons dice, or even by pasting exercise numbers to random items and pulling them out of a bag.

(c) Home practice

- Regular home practice: Kids who do daily home practice, even just for a few minutes, seem to improve more than those that don’t.

- Using technology to make home practice easy: Historically, most of our resources were pen and paper – we killed many trees – and filled many ugly scrap books. Now, for many clients, we use iPads and digital resources. We share condensed packs of organised materials, usually composed of all the target words on one page, sound cards, carrier phrase lists, and an mp3 auditory bombardment file recorded by us that can be played straight from a device or in the car. For children with language and/or phonological awareness deficits, we often also share picture books for shared reading, and high quality audiobooks. Increasingly, we give clients access to our online libraries of resources to keep practicing between therapy blocks and after therapy.

(3) The child and family in front of us

No speech treatment works for all clients or families in all conditions. At intake, we look at known risk factors, such as family histories of speech difficulties, gender, and hearing issues. During the initial assessment, we evaluate the client’s language skills so that we can explain what we are doing in a way the client can understand. To make treatment recommendations to families after the assessment, we consider the nature and severity of the client’s speech disorder, the child’s age, when the child is going to start school, the success (or failure) of any previous therapy, and the child’s motivation, attention, and interests (Kamhi, 2006).

In therapy, we try to use the child’s current speech strengths and abilities. We need to have a good idea about the amount of support we will need to give the client to stay focused and motivated to work on difficult speech tasks (Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1994). For some children, we need to get creative and use the child’s interests to encourage them to do the work. That’s why I know way too much about Pokemon and sharks, Disney Princesses and scorpions, dinosaurs and pirates, Minecraft and Roblox, Batman Lego and semiprecious stones, diesel trains and NBA basketball.

We need to know what the family thinks about the child’s speech and speech therapy. The level of concern a parent has can play an important role in whether the child is assessed, attends therapy, and does the work between sessions (Kamhi, 2006).

We need to answer questions – even when the answer is ‘I don’t know’. Whenever we get asked a question a second time, we try to write an article about it to share with clients. For example, children’s speech development can be affected, at least temporarily, by chronic middle ear infections or other types of conductive hearing loss. Tonsil and adenoid problems can affect speech clarity, as can allergies, colds and other things that leave kids with blocked noses. Sleep disorders can affect language development. Stuttering and cluttering can make speech hard to understand. Rate control issues can reduce intelligibility. Bilingual children are learning two speech sound systems. Braces can cause mild speech distortions for a while; and some older children continue to have residual speech difficulties that have social and work implications. Some people think that tongue ties and sucking a dummy for too long or thumb sucking affect speech development, but I’m not convinced (based on the evidence to date).

For time, logistical or financial reasons, some of our clients can only attend therapy once a fortnight or less frequently. This can be a challenge, e.g. for motor speech treatments that require high treatment dosage.

Some of our clients have other health issues, like hearing problems, attention difficulties or sleep disorders. For some clients, speech isn’t always the family’s highest priority – the client may have other health challenges, or simply be focused on other goals that are important to them, e.g. sport or music. Many of our clients have more than one communication challenge (e.g. speech disorders plus stuttering, language difficulties, social difficulties, voice problems, and/or dyslexia).

We have to consider all these issues and tailor our therapy to each client and family. Again, this is difficult, but it’s our job.

Clinical bottom line

Lots of elements go into providing good speech therapy. Research, clinical experience and information about clients and their goals all need to be integrated to provide evidence-based, quality care.

In this article, we’ve tried to explain what we do in speech therapy and why we do it. We’ve identified some things that we think make a difference in our client’s results to date. But we need to keep reading new research, improving our systems and resources, training ourselves in new techniques, measuring our results, and sharing information with families about new developments to do our job properly. Most importantly, we need to work with families and children with speech sound disorders to make sure they know what we are doing and why, and to do all we can to ensure our therapy works for them.

Principal sources:

As always, any errors of interpretation are mine alone.

- Baker, E., Williams, A.L., McLeod, S., & McCauley, R. (2018). Elements of Phonological Interventions for Children with Speech Sound Disorders: the Development of a Taxonomy, American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27, 906-935. This is an incredibly useful article, and provided a framework to explain our current clinical practices. Every speech pathologist treating children with speech sound disorders should read it.

- Rvachew, S. (2017). How effective is phonology treatment?, last accessed on 17 May 2020, available here. This short article asks (then answers) the important question: do we really want to know whether the child’s rate of change is bigger during treatment than it was when the child was not being treated? The answer is of course ‘yes’, and I use the insights in this article to set measurable goals for my clients.

- Kamhi, A. (2006). Treatment Decisions for Children with Speech-Sound Disorders. Language, Speech and Hearing in Schools, 37(4), 271-279. I first read this article several years ago when I was struggling to understand why the treatment approach didn’t seem to make much difference to my clients’ outcomes. It provided a framework that helped us design our intake, assessment and reporting procedures to integrate research, client and clinical factors.

- Baker, E., & McLeod, S. (2011). Evidence-Based Practice for Children with Speech Sound Disorders: Part 1 Narrative Review, Language, Speech, and Hearing in Schools, 42, 102-139.

- Baker, E., & McLeod, S. (2011). Evidence-Based Practice for Children with Speech Sound Disorders: Part 2 Application to Clinical Practice, Language, Speech, and Hearing in Schools, 42, 140-151.

- Shriberg, L.D., Fourakis, M., Hall, S.D., Karlsson, H.B., Lohmeier, H.L., McSweeny, J.L., Potter, N.L., Scheer-Cohen, A.R., Strand, E.A., Tilkens, C.M., & Wilson, D.L. (2010). Extensions to the Speech Disorders Classification System, Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 24(10), 795-824.

Related articles:

- Important update: In what order and at what age should my child learn to say his/her consonants? FAQs

- FAQ: 10 common speech patterns seen in children 3-5 years of age – and when you should be concerned

- My child’s speech is unclear to adults she doesn’t know. Is that normal for her age? (An important research update about child speech intelligibility norms)

- How to treat speech sound disorders 1: the Cycles Approach

- How to treat speech sound disorders 2: the Complexity Approach

- How to treat speech sound disorders 3: Contrastive Approach – Minimal and Maximal Pairs

- Beyond flashcards and gluesticks: what to do if you or your 9-25 year old still has speech sound issues

- How to use principles of motor learning to improve your speech

- FAQ: Lisps

- How to identify and treat young children with both speech and language disorders

- My pre-schooler stutters and has problems with speech sounds: which one should I treat first?

- ‘He was such a good baby. Never made a sound!’ Late babbling as a red flag for potential speech-language delays

- Why preschoolers with unclear speech are at risk of later reading problems: red flags to seek help

- 12 speech-related warning signs that your child might have a hearing problem

- Will tongue-wiggling, blowing bubbles, or making funny faces help my child to speak more clearly?

- Childhood Apraxia of Speech: FAQs and treatment update

- Up-skilling to Treat Severe Childhood Apraxia of Speech (including free training links)

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.