Almost everyone recommends that parents should read picture books to their young children every day. Teachers, early learning professionals, speech pathologists, literacy experts, librarians, psychologists, doctors, authors – even celebrities.

But why?

Reading with young kids is associated with:

- better language outcomes (e.g. Arterberry, et al., 2007; Demir-Lira eta al., 2018; Fletcher & Reese, 2005); and

- better literacy skills (e.g. Bus et al., 1995; Deckner et al., 2006; Lonigan et al., 2000; and Schahaeian et al., 2018).

But why?

- Picture books contain more unique words than the type of speech most parents normally use when speaking with their children (Hayes & Ehrens, 1998; Massaro, 2015; Montag et al., 2015).

- When reading picture books with young children, parents provide kids with more speech input and use more sophisticated words than in other activities (e.g. Craig-Thoreson et al., 2001; Salo et al., 2016; Weizman & Snow, 2001).

- Frequent shared book reading in the home is associated with increased vocabulary for children (e.g. Farrant & Zubrick, 2012).

- The average picture book contains around 680 words. If you read one book a day to your child that has, say, 600 words in it, your child will hear almost 220,000 words of text a year. If you read two books a day, your child will hear almost 440,000 words of text a year (Montag et al., 2015) – somewhere between 3-6% of the words that a typical child hears everyday; but up to 10% of the total words that children from low socioeconomic backgrounds hear (on average) (Weisleder & Fernald, 2014).

When listening to picture books children hear words they would not otherwise hear, or might hear less often.

So is it just about hearing new words?

No. Far from it:

- Shared book reading includes frequent instances of joint attention. Joint attention is known to underpin language learning for children (Fletcher et al., 2008; Farrani & Zubrick, 2012). For some practical tips on how to improve your shared reading skills, check out our article here.

- In everyday speech with young children, we tend to talk about the “here and now”. When parents read picture books to infants and young children, the books tend to introduce language relating to different places and times (Montag et al., 2015).

- Many children find shared book reading pleasant and comforting – we all tend to learn better when we feel safe and supported (e.g. Baker et al., 1997).

- When reading books with young children, parents read the text, but also point to and label pictures, paraphrase text, expand on and comment on the book, ask and answer questions, and engage in a range of other extra-text speech (e.g. Deckner et al., 2006; Fletcher et al., 2008).

- Picture books may be an important source of some types of complex language that parents don’t usually use with their kids outside of book-reading.

- Most picture books for infants and preschoolers follow a narrative structure, which may help children learn to understand story telling conventions and to use language in discourse for the purposes of telling a story (e.g. Sulzby, 1985).

- Books often contain more syntactic complexity than speech (e.g. Montag & McDonald, 2015).

- Picture books may be an important source of complex sentences (e.g. sentences containing subordinating conjunctions like because, if, while, before or after (Cameron-Faulkner and Noble, 2013).

- Compared to normal conversation with children, picture books, on average, contain more examples of passive sentences (e.g. “The milk has been poured.”) On average, picture books contain one passive sentence.

- Compared to normal conversation with children, picture books, on average, contain more examples of relative clauses (e.g. “What’s the animal that we saw at the zoo?”, “This is the house that Jack built.”, “I like the photo that is on the kitchen wall.”, “The children who walk to school every day are very fit.”) (e.g. Montag, 2019).

- There are strong links between exposure to rare and complex sentence types and subsequent comprehension and use of complex sentence types in children and adults (Clark, 2003; Diessel & Tomasello, 2000). This suggests that there may be a link between exposure to complex sentences, and understanding and using them.

Bottom Line

We all know that reading picture books with our young kids is a good idea. About half of parents with children aged over 12 months report reading to their children every day (e.g. Raikes et al., 2006); and parents who are older and university graduates often read to their toddlers on average twice a day (Deckner, 2006).

About a quarter of parents report rarely or never reading with their children (e.g. McAdoo & Carcia Coll, 2001). Understanding why reading books is so important may help encourage parents to give it a go. But there are of course a host of complex socio-economic, cultural, access, and other reasons why some parents find it hard to do it (For example, the average likelihood of reading to infants and preschool children reduces with lower socioeconomic status (Bradley et al., 2001)).

It’s never to too late to start reading books with your children. Your local library can be a great place to go for ideas and books.

Need inspiration to get going?

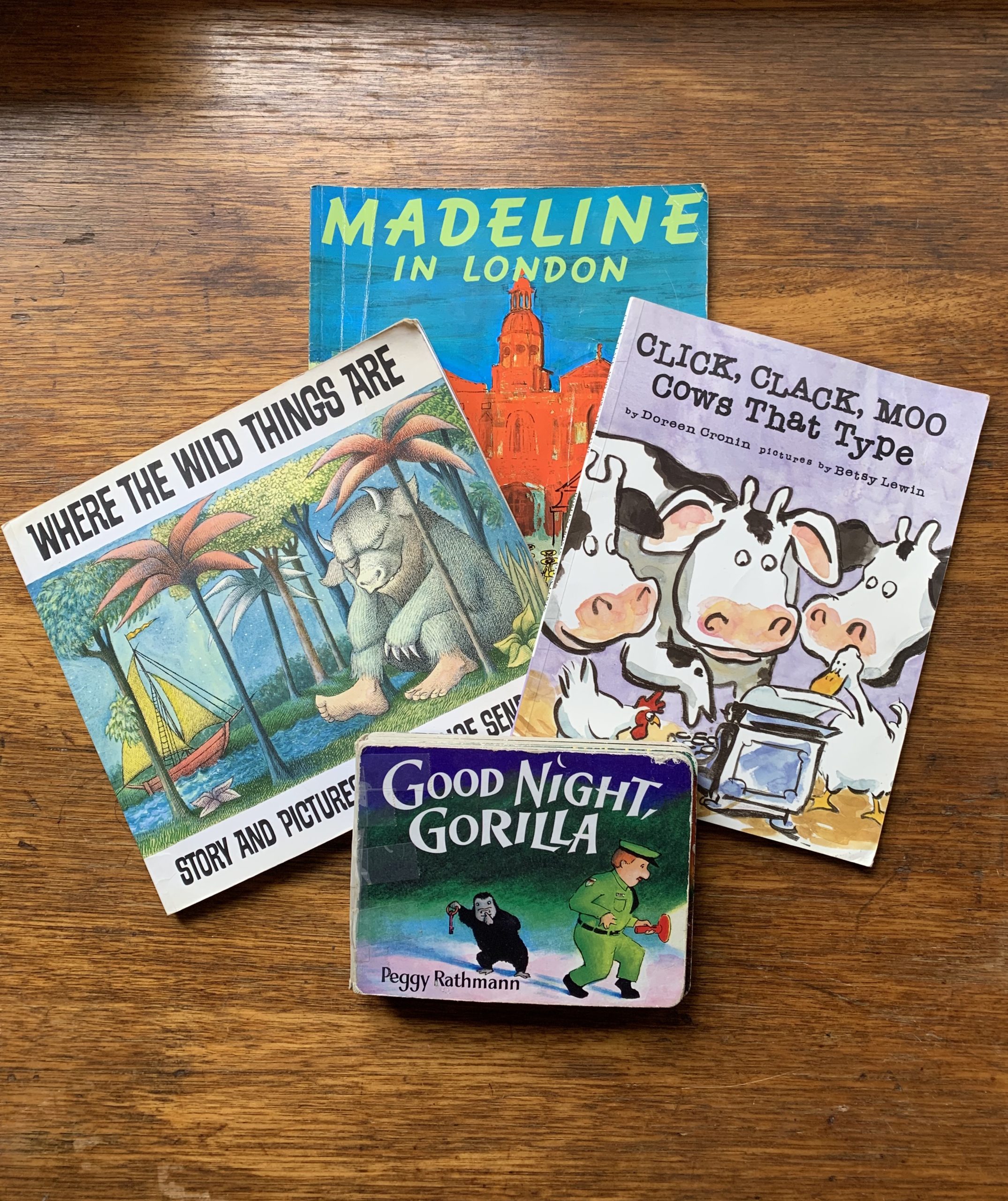

We are living in a Golden Age for picture books. It can be hard to know where to start. We’ve written about some of our favourite picture books here. But here is a short list of 10 classic books I used to love reading with my kids, and that I’m currently sharing regularly with my younger clients:

- “Are You My Mother?” by P.D. Eastman

- “The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein

- “Click Clack Moo: Cows that Type” by Doreen Cronin

- “Dear Zoo” by Rod Campbell

- “Good Night, Gorilla” by Peggy Rathman

- “Madeline” by Ludwig Bemelmans

- “Oh, the Places You’ll Go” by Dr. Seuss

- “The Pigeon finds a Hot Dog!” by Mo Willems

- “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” by Eric Carle

- “Where the Wild Things Are” by Maurice Sendak

You will find most of these on ‘all time best children’s books lists’, and most libraries have multiple copies. You can also find videos of people reading these books on YouTube, although I prefer sharing physical books with children for some of the reasons outlined above.

Principal sources:

Montag, J. L. (2019). Differences in sentence complexity in the text of children’s picture books and child-directed speech. First Language, 39(5) 527-546.

Montag, J.L., Jones, Michael N., Smith, L.B. (2015). The Words Children Hear: Picture Books and the Statistics for Language Learning, Psychological Science, 26, 1489-1496. This article contains an excellent list or “corpus” of children’s books. By luck, all the books I recommend above are on it, as well as 90 others.

Related articles:

- Reading with – not to – your pre-schoolers: how to do it better (and why)

- Books with verbs to level up your child’s language development: 24 of the best

- More verb-charged books to ignite your child’s language development

- 13 tried-and-tested stocking-stuffer books for preschoolers

- Read non-fiction books to your late talkers and preschoolers: here’s why

- Why poor kids are more likely to be poor readers (and what we can do about it)

- Speaking for themselves: why I choose ambitious goals to help young children put words together

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.