How to improve exam results: 9 free evidence-based DIY strategies

I can’t cook, read blueprints, or dress with style. But I’m good at exams. Not because I’m special or gifted. My “secret” is boring and simple:

As a young adult, I learned how to study properly.

For more than 100 years, education and health academics have been researching study techniques to figure out which ones work the best. Unfortunately, they haven’t been very good at sharing their findings with teachers, therapists or the general public. The people who tend to read the research closely are those making lots of money running tutoring “academies”.

We’ve talked about evidence-based reading comprehension strategies here and here. But, in practice, many of us use a variety of reading comprehension and study skills together when preparing for exams (e.g. see Hock & Mellard, 2005).

A. Information about effective studying strategies should be free!

In this article, I want to share 9 evidence-based techniques I use to learn things for exams. They’ve helped me succeed in more exams, tests and quizzes than I’d care to remember over the years, including for my (ancient) Higher School Certificate and three University degrees.

They work.

I’ve chosen strategies that can be put into action by students without much outside help and without cost. And I’ve based my choices on things that:

- have worked for me; and

- are supported by peer-reviewed research.

I’ve sorted the strategies from most useful to least useful based on the evidence and my experiences. For evidence summaries, I’ve drawn from the excellent 55-page monograph by Professor John Dunlosky and colleagues published in 2013 (citation below, errors of interpretation are my own).

Note: These tips work best for tests of knowledge/content/subjects (e.g. Maths, English, Anatomy), rather than tests of intelligence or personality (e.g. psychometric IQ tests) or motor skills (e.g. piano-playing or speech).

B. 9 effective, evidence-based study strategies

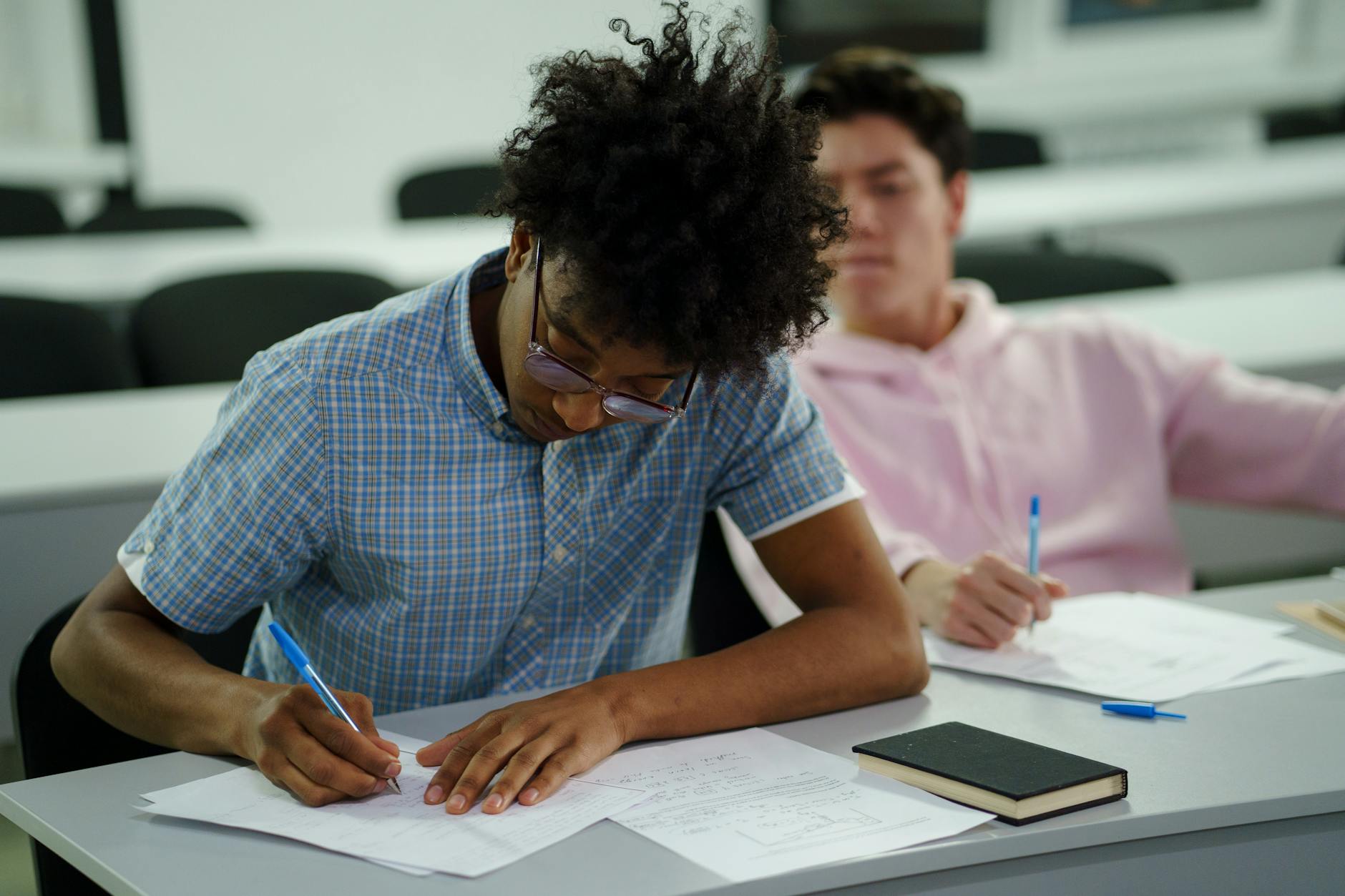

1: Do practice tests

What is it? Practice testing is low- or no-stakes practice doing “tests” outside of class. It includes doing mock tests and activities where you practice recalling information, e.g. answering questions at the end of text-book chapters or using real or virtual flashcards to “test” your recall of knowledge.

Why does it work? No-one likes doing tests and people tend to avoid them where ever possible. This is a real shame because we’ve known for a long time that testing improves learning (e.g. Abbott, 1909). Practice testing helps you remember things (e.g. Rawson & Dunlosky, 2011). We think testing has two effects:

- direct: improving the retention of information by triggering “elaborative retrieval processes”. In other words, testing yourself forces you to search your long-term memory, which activates related information, and forms an association between the information you are attempting to retrieve and information already in your long-term memory (e.g. Carpenter, 2009); and

- indirect: forming connections between the cue (question) and the response (answer) when you re-study, which helps you to remember the answer when asked the question in the real test (Pyc & Rawson, 2010).

How to do it? If possible, get your hands on practice tests that are similar to the exam you will be taking. Look for publicly available/free versions before spending money. You can also create your own flashcards with questions on one side and answers on the other (there are lots of free and low-cost options to create virtual flashcards online, e.g. Anki, which also uses the next strategy). Or you can adopt the Cornell note-taking method, which involves leaving a blank column when taking notes in class and entering key terms or questions in it shortly after taking notes to use for self-testing when reviewing notes at a later time (e.g. Pauk & Ross, 2010).

With any system or method, you want clear feedback on whether your answers are right or wrong, so make sure you write the complete correct answers on the back of the flashcards and look for model answers to go with practice exams.

Real world examples: When studying for my Hong Kong conveyancing exam, I did five practice tests, carefully comparing my responses to the model answers. The exam has a notoriously high failure rate (at the time reported to be about 70%) and my studying was interrupted by a burst appendix. I managed to pass the exam – mainly due to all the practice tests I’d done. Another example: when learning phonetics, short “no-stakes” practice tests in class every day shocked me into improving my transcription skills from zero to semi-competence in six weeks.

Usefulness: High. Studies show that practice testing is more effective than concept mapping, note-taking, imagery use, and re-reading.

2: Space out your study (distributed practice)

What is it? Distributed practice is a fancy way of saying “spread out your study over time”.

Why does it work? We all procrastinate, which means we all cram to some degree. And cramming works better than not studying at all. But distributing learning over time helps you to remember things more than by cramming sessions together. There’s a few theories about why distributed practice works. One argues that our processing of information in a second session suffers when it is in close to time to the original session, basically because we don’t have to work hard during the second session, which makes us think we remember more than we do (Bahrick & Hall, 2005).

How to do it? There is no one size fits all answer. But there is some evidence that the lag time should be about 10-20% of the desired retention interval. For example, to remember something for one week, study sessions should be spaced about one or two days apart. To remember something for 5 years, you should revise it every 6 to 12 months (Cepeda et al., 2008). For big exams (e.g. the Higher School Certificate), intervals of a month or even more may be ideal for studying core content that needs to be retained, especially where the exam is testing knowledge gained across several years of education.

Real world example: When I was studying speech pathology, there were a number of key principles of assessment and intervention that applied to different subjects. By revising these principles once a month or so, I found them easy to recall at will during exams. I still recall and use them in practice.

Usefulness: High. It’s been shown to work with students of different ages with a wide variety of subjects. It’s easy to put into practice once you know how to do it.

3: Channel your inner 3-year old and ask “why, why, why?” (elaborate interrogation)

What is it? Asking “why?” about what you’re reading.

How to do it? For example, read this sentence: “The hungry man got in the car”.

Now ask yourself: “Why did the hungry man get in the car?”

If, like me, you answered the questions with something like: “So he could go to the restaurant”, or “So he could go through drive thru”, congratulations, you’ve successfully used the technique. Easy, right?

(Across different studies, there are a few variations of the basic question we ask ourselves. It can be “Why?”, “Why does it make sense that…”, or “Why is this true?”. I prefer to just ask “Why?”)

Why does it work? The most credible explanation is that asking “why” forces us to integrate new information with existing prior knowledge. We took the new information (“The hungry man got in the car”) and combined it with what we know about hungry people who get in cars. In a study, over 70% of people who used this technique were able to recall that the man got in the car, compared to about 40% of people who were told the man got in the car to go the restaurant and 40% of people who simply read the sentence (Pressley et al., 1987).

Real world example: I must confess, I don’t use this strategy as much as I should. As a thought-experiment, I used it to review the Dunlosky paper, and found I could remember many of his key findings without needing to re-read the paper. I’m going to try it out more often.

Usefulness: Moderate. It doesn’t require much training, if any. It’s most useful when dealing with lists of factual sentences. It’s not as useful when dealing with more complex texts, e.g. about a process or system. For the strategy to work, you need to use it frequently. One prompt per page or two is not enough.

4: Explain it to yourself in Plain English (self-explanation)

What is it? Explaining how new information is related to known information, or explaining steps taken during problem solving.

How to do it? Simply pause after reading a sentence or paragraph and ask yourself questions like “Explain what that sentence/paragraph means to you?”, “What new information does this sentence give you?” or “How does it relate to what you already know?” Alternatively, explain the steps you are taking to solve a problem as you solve it.

Why does it work? As with asking yourself “Why?”, we think self-explanation helps integrate new knowledge with existing knowledge to aid learning and recall (e.g. Berry, 1983).

Real world example: I use this technique when preparing to answer case-based questions. It’s particularly useful for tasks where you are asked to explain technical, jargon laden concepts/results in Plain English with no pointless long words. If you can’t explain what you’ve read to yourself, you have no hope of explaining it to someone else, especially when under exam pressure.

Usefulness: Moderate. The strategy has been shown to work across lots of different types of texts and tasks. But we don’t know how long the learning lasts. And it can take a long time to do well, which reduces its usefulness when you are pressed for time or in an exam.

5: Mix and match study problems (interleaved practice)

What is it? Mixing different kinds of problems or materials within a single study session.

How to do it? For example, you might practice trigonometry, geometry and calculus problems in a single session. Or you might tackle three or four kinds of legal problems focusing on different rights and remedies.

Why does it work? We’ve known for a while that mixing activities can improve motor learning in some conditions (e.g. Wulf & Shea, 2002). There’s growing evidence that it might also work on cognitive tasks like learning for exams. One theory is that mixing up different kinds of problems with a single session helps students distinguish between different kinds of problems so they can apply the right strategies for each in a test (e.g. Rohrer & Taylor, 2007).

Mixed practice may promote organisational processing because it allows students to compare different kinds of problems more readily. It’s also possible that mixed practice creates distributed learning conditions, which help students retain information and learn more effectively (see strategy 2, above). Mixed practice is also more akin to true test conditions than working sequentially through kinds of problems, which may create results like practice testing (see strategy 1, above).

Real world example: When studying for an anatomy exam, I shuffled my head, neck, hearing and lung-related notes/cards to randomise the key kinds of questions I was asking myself based on the format of previous exams. This enabled me to use strategies 1, 2 and 5 together.

Usefulness: Moderate. Results to date suggest that mixed practice may have dramatic results on learning maths skills. In a study comparing students doing one type of problem versus children doing four kinds of problems per session, children working on one kind of problem at a time tended to do better during practice. But this reversed dramatically when the skills were tested later, with the “mixed problem” students outperforming the “single problem” students by more than 40% (Rohrer & Taylor, 2007). But the research base is fairly limited to date, and we don’t know how much practice of a particular skill is required before mixed practice will help. In my example, I was already fairly comfortable with the content of the topics to be examined before I randomised the questions.

6: Link words to vivid images to help cue and remember the answers (key-word mnemonics)

What is it? Using key-words and mental imagery to associate words and concepts. This is an “oldie but a goodie”, dating back at least to the Ancient Greeks (Yates, 1966).

How to do it? For example, just say you are trying to learn the French word for tooth (la dent). You would develop a vivid mental image of the English key-word (tooth) somehow interacting with the French translation (la dent). For example, you could imagine a lady dentist pulling out a tooth and giving it a big dent with a big red ladle, to make a la-dent in the tooth. The more vivid and silly (and hence memorable) the image, the better!

Why it works? The power of this technique lies in its use of interactive images – images that link the cue with the target. The technique has been shown to work with foreign-language vocabulary, definitions of scientific terms, state capital memorisation, elements of the periodic table (e.g. Jitendra et al., 2004).

Real world examples: I have used the technique successfully to memorise several lists of words and concepts over the years, from case names lists for law exams, to the capitals of countries (for a trivia competition), to cranial nerve pathways (for a speech pathology exam), to Bahasa Indonesian vocabulary (for something to do while stuck in transit on a business trip). As per the studies quoted above, I have found the technique quite time and labour intensive, and less useful for abstract, dynamic or complex topics. I have also found that long-term retention requires upkeep/practice – if you lose the image, you can lose the cue and target, too. Don’t ask me anything in Bahasa Indonesian, for example!

Usefulness: High for memorising word lists for short periods; low generally: For “key-word friendly targets” like the examples above, it can be very useful. e.g. for learning lists of concrete nouns quickly. But it takes lots of time to learn to do it well, and some evidence suggests it does not lead to long-term retention of information (e.g. Fritz et al., 2007).

7: Imagery for text learning

What is it? Attempting to form mental images of text materials when reading or listening.

How to do it? As you listen or read, e.g. to a story, consciously create a mental image of what’s happening. Try to imagine the sights, sounds, smells, and textures of the “world” around you.

Why it works? Developing images about what you are hearing/reading can improve your mental organisation and integration of the text (e.g. Hunt, 2006). Using prior knowledge of the world to generate a picture of a story may also improve your understanding (e.g. Leutner et al., 2009). This technique may work better for listening tasks than for reading tasks (Brooks, 1968). But it’s one thing to tell yourself to visualise something; it’s another to actually do it (Anderson & Kulhavy, 1972).

Real world examples: I tend to use this when reading fiction for pleasure to enhance my comprehension of the details (otherwise I find myself skimming!). I used it for English exams back when I was in high school. It takes some practice to learn to “see”, “hear”, “smell” and “feel” what the characters are feeling. And, because I’m not particularly good at manipulating images in my head, I tend to use other strategies when under pressure in exams.

Usefulness: Low. The strategy seems to have a wider scope of potential use than key-word mnemonics. However, the benefits of the technique are limited to image-friendly materials and, like key-word mnemonics, may fade over time without upkeep.

8: Summarising

What is it? Writing summaries of texts.

How to do it? Read the text, identify the main points, discard the less important information, and capture the gist (Brown et al., 1981). Sounds easy in principle!

Why it works? We think summarising boosts learning and retention because it involves paying attention to what you are reading and extracting the higher-level meaning and gist of the material (Bretzing & Kulhavy, 1979). It also boosts organisational processing because it makes us connect the ideas in a text to each other. Writing about the important points in your own words produces a benefit over and above simply selecting the important information (e.g. Chi, 2009).

Real life example: When studying for my closed book law exams, I often prepared one paragraph summaries of each case on my case list, usually following a set format (e.g. case/parties names, year, judge, key issues/why memorable, main decision). I would then prepare a summary of the summary, e.g. “Donoghue v Stevenson – 1932 – Lord Atkin, House of Lords – Snail in the Bottle Case – negligence – duty of care/neighbour principle.”

Usefulness: Low. Even though making summaries sounds sensible, and is a well-known reading comprehension technique, the usefulness of the strategy for exam preparation depends on how well you can summarise. If you summarise the wrong things, the strategy can backfire. Many learners need training to summarise well, which makes the strategy less accessible than some of the others mentioned above. We’ll tackle the fine art of summarising in a future post.

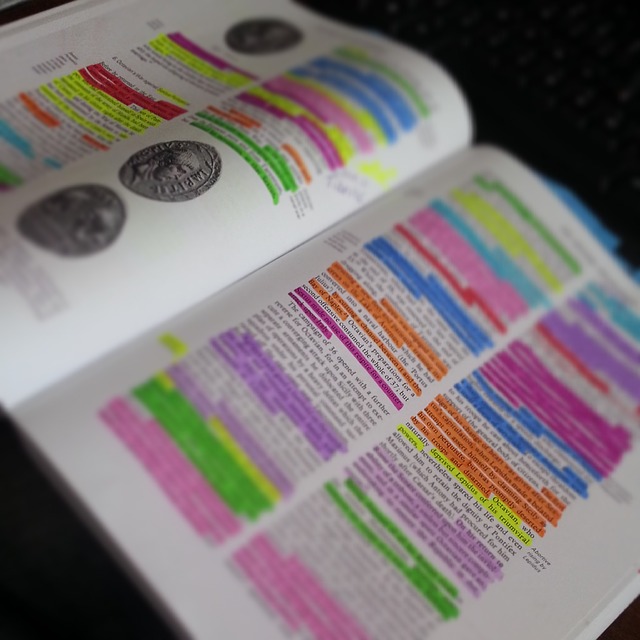

9: Highlighting/underlining

What is it? A favourite of students!

How to do it? with a highlighter or pen, mark potentially important parts of the text when reading.

Why it works? Researchers cite the isolation effect (e.g. Hunt, 1995). For instance, if you are given this list: “goat, pig, table, chicken, cow”, you will be more likely to recall “table” than if you had been asked to remember it in a list of furniture. By analogy, highlighting or underlining text causes it to “pop out” from the rest of the text, making it easier to remember (e.g. Lorch, 1989). Another theory is that the effort of actively selecting information should benefit memory more than simply reading it (e.g. Faw & Waller, 1976), which seems a better explanation to me.

Real life examples: I’m an habitual highlighter! Despite its relatively low-level of evidence, I can’t help it and now find it difficult to absorb technical information without highlighting the key points. I used to highlight way too much and have taught myself to focus on main points, and to asterix points requiring follow-up or further thought.

Usefulness: Low. In many studies, highlighting has been shown to do little to boost performance. The quality of the highlighting is crucial to whether it helps students learn (e.g. Wollen et al., 1985); and many students mark too much or too little (e.g. Idstein & Jenkins, 1972). Training students to highlight more effectively (e.g. looking for main ideas before highlighting, and underlining as little as possible) may help (e.g. Hayati & Shariatifar, 2009), but this reduces the accessibility of the strategy without special training. Disturbingly, there is some evidence that highlighting may actually hurt performance on high level tasks like reading between the lines (i.e. inferencing) (e.g. Peterson, 1992).

C. Clinical bottom line

Learning to use effective studying techniques can help students improve their test results. But lots of students aren’t taught which strategies work, and may end up using techniques with a low-level of evidence, e.g. highlighting indiscriminately or simply re-reading texts they are meant to learn. Most of the study strategies summarised in this article are easy to put into action – even for students in upper primary school. If used properly, these techniques can help students accomplish their academic, work and life goals.

Related articles:

- Back-to-school study skill: 3 steps to remember any 10 things in order

- Want better school results? Avoid the hype and use free, evidence-based learning strategies

- Worried about the HSC? 8 practical (and free) things you can do this week to get ready

Key source: Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.A., Marsh, E.J., Nathan, M.J., & Willingham, D.T. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning with Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions from Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1) 4-58. This is an excellent read and contains lots of useful details that I couldn’t capture in an article like this.

Images: http://tinyurl.com/z4zttut, http://tinyurl.com/zm7ae9d, http://tinyurl.com/gs3fo43 and http://tinyurl.com/gogaw2p.

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.