We get asked this question a lot. Until very recently – we’ve had four main problems answering it properly:

- no published studies comparing the two programs head-to-head*;

- generally lower quality evidence for the Westmead Program (see below);

- most of the high-quality, published studies about both the Lidcombe Program and the Westmead Program have been carried out in specialist university clinics (rather than in community and private practice clinics); and

- most of the kids in the high-quality studies have not had any communication issues other than stuttering, e.g. speech sound disorders or developmental language disorders**. This has sometimes made it hard to apply the research to our “real world” case load.

A. New research

A new study has been published that – to an extent – allows us to answer these questions with more confidence.

B. Lidcombe and Westmead Programs – the basics

We’ve written at length about the Lidcombe Program and the Westmead Program for preschoolers who stutter. We’ve included links to many of our previous articles below.

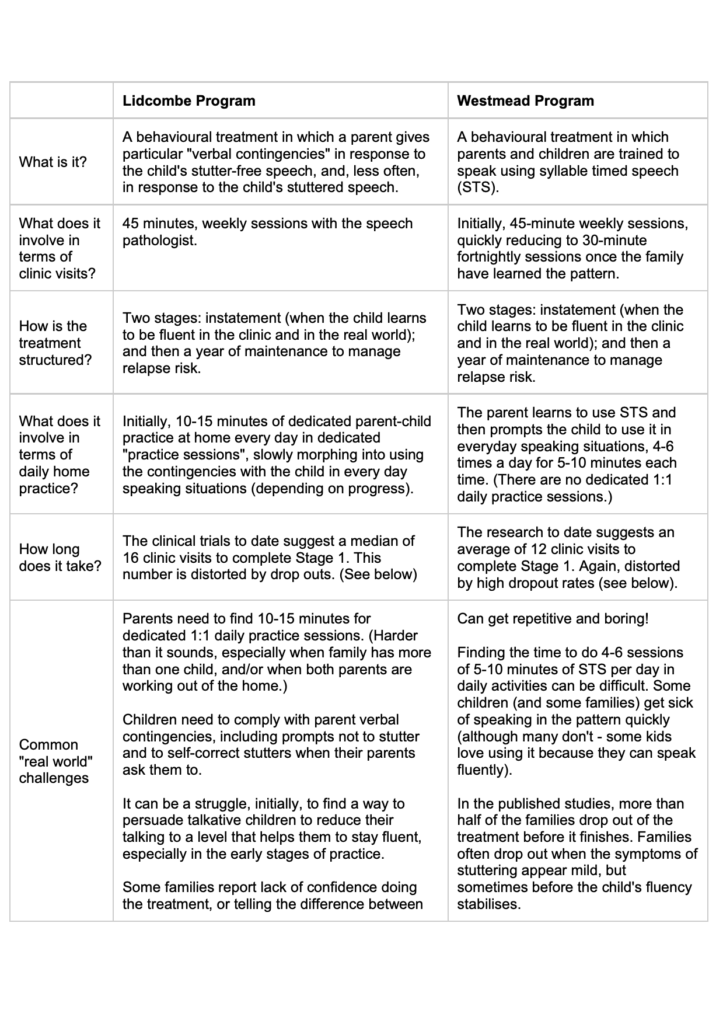

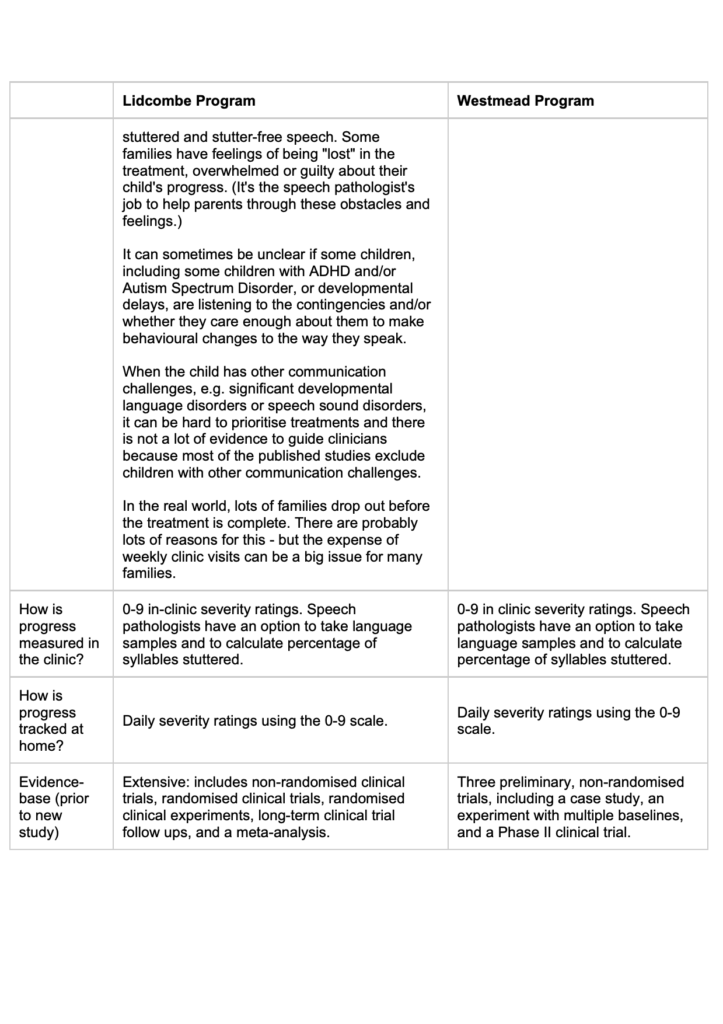

Before looking at the new evidence and its clinical implications, let’s recap some of the main elements of each treatment:

C. New study: so how do the treatments stack up head-to-head?

Dr Natasha Trajkovski (the lead author in most of the published Westmead Program studies to date) and colleagues have published the results of a three-arm randomised controlled trial of the Lidcombe Program and the Westmead Program.

Participants were 91 pre-school children (61 boys, 30 girls), aged 5 years, 11 months or younger. A number of participants also had other language, speech and developmental disorders: in other words, the population studied was much more like the one I see in the real world in my clinic.

The children were randomised to one of three different groups:

- Lidcombe Program (33 children);

- Westmead Program (28 children); and

- a slightly different version of the Westmead Program, including Lidcombe-style verbal contingencies, and contingencies for STS, which was similar in many respects to the school-aged hybrid treatment we write about here (30 children).

(Given the most effective “window” for treating stuttering is during pre-school years, and the social, mental health, and other costs of stuttering, it would have been unethical not to treat some children or to give one group a placebo.)

Interestingly, the treatments were delivered across four sites in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia: two university research clinics, and two community clinics. The inclusion of community clinic-based speech pathologists (in addition to research clinicians) makes the study conditions more like the “real world”.

Each participant’s stuttering severity was independently assessed at nine months after they had been randomised to treatment groups, and stuttering was measured by percentage of syllables stuttered. The study also looked at how many clinic visits it took for the children to complete Stage 1 of each treatment.

D. Key findings

(a) Drop outs were very significant:

- 27.3% of the Lidcombe Program families dropped out;

- 42.9% of the Westmead Program families dropped out; and

- 43.3% of the Hybrid treatment families dropped out.

The research team suggested three factors that may have contributed to the high drop outs rate:

- around one-third of the kids were treated in community clinics: families who sign up to university clinic-based research may be more likely to stick with it;

- no exclusion criteria: some of the kids had other speech, language and developmental challenges and these children may not have responded as quickly as children in other studies who stuttered but had no other issues; and

- 13 of the kids in the trial were younger than 3 years of age. Toddlers tend to be less compliant than older kids!

(b) At 9 months post-randomisation, there were no statistically significant differences in stuttering outcomes for those kids who didn’t drop out:

- 1.35% syllables stuttered for children treated with the Lidcombe Program;

- 2.02% syllables stuttered for children treated with the Westmead Program; and

- 1.99% syllables stuttered for children treated with the Hybrid Treatment.

(c) It took much longer on average for children treated with the Lidcombe Program to complete Stage 1 of the treatment. The median number of clinic visits required for Stage 1 was:

- 30 (range 7-47) for the Lidcombe Program;

- 18 (range 9-28) for the Westmead Program; and

- 16 (range 4-34) for the Hybrid Treatment.

However, this ignores the much higher rate of drop outs for the Westmead Program.

E. Our key clinical takeaways

- Compared to previous studies carried out in University clinics with children who stutter but have no other issues, this study is much more applicable to our real world case load. Many of the children we see who stutter also have speech and/or language issues and some of the kids we see have other developmental issues as well.

- The new study gives us more confidence in continuing to offer families the option of Lidcombe, Westmead and Hybrid treatments. It also allows us to give families more informed choices when it comes to tailoring treatments to the needs of each child and family.

- The new study allows us to level with families about how hard it is to stick with a treatment right from the start, and to work together to make treatment more relevant and engaging for clients (and their families).

- We can now give families some better information about how many clinic visits to expect for each treatment – a very important consideration when parents are accessing private services.

- For very talkative kids, kids with attention and/or other behavioural issues, and really busy families who signal during assessment that they will struggle to find time to do the Lidcombe Program, this study gives us more confidence to recommend the Westmead Program with contingencies for stutter free speech as a first option (rather than first trialling and struggling with the Lidcombe Program).

- For kids with significant language disorders as well as stuttering, the new study does not suggest we need to change our recent clinical practice of combining shared reading, sentence-level expressive language and verbal reasoning tasks with syllable timed speech practice, and Lidcombe-style contingencies for smooth talking (i.e. a structured hybrid approach). We have found that varying expressive language tasks in the clinic with syllable timed speech increases compliance, and can make home practice easier to complete for busy families – especially verbal reasoning tasks that lead naturally to everyday conversations, e.g. in the car. We adopted this practice partly in response to evidence suggesting that the rate of a child’s language development may be a predictor of stuttering recovery.

- We welcome efforts by the Australian Stuttering Research Centre (ASRC) and others to support families of preschoolers who stutter by addressing real world obstacles to completing treatment. For example, we are very excited about the ASRC’s current project to develop an internet version of the Westmead Program.

Related articles:

- The Lidcombe Program for children who stutter

- The Westmead Program for children who stutter

- Stuttering: will my child recover? Factors that predict recovery and why you shouldn’t wait

- My child stutters. Is it because he’s shy? sensitive? hyper?

- Stuttering: what do we mean by ‘recovery’?

- Parent dilemma: What to do if your child stutters and has speech sound problems – research update

- Stuttering treatments: what works for whom? An evidence update

- My school-aged child stutters. What should I do?

- School-age stuttering research update: mixing and matching treatments to get results

- Why does the Lidcombe Program for stuttering work: a case of “words will never hurt me”?

- The Lidcombe Program for stuttering: my 10 favourite therapy activities

- Lidcombe Program Stuttering Activities, Volume 2 (low-prep printable activities for face-to-face and Skype therapy)

- Child developmental language disorders

- Child speech sound disorders

For more information about the Lidcombe and Westmead Programs, visit the Australian Stuttering Research Centre website.

Principal source: Trajkovski, N., O’Brian, S., Onslow, M., Packman, A., Lowe, R., Menzies, R., Jones, M., & Reilly, S. (2019). A three-arm randomised controlled trial of the Lidcombe Program and Westmead Program early stuttering interventions. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 61 (September). See: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfludis.2019.105708

* For completeness, note there is a published randomised trial comparing the Lidcombe Program and another program called the Rotterdam Evaluations Study of Stuttering Therapy (RESTART), which also reported no statistically significant difference in outcomes between the treatments (De Sonneville-Koedoot et al., 2015).

** Dr Kate Bridgman, a leading stuttering researcher, pointed out to me via Twitter on 9 July 2019 that some of the more recent Lidcombe Program randomised-controlled trials also did not exclude children who stuttered and also had speech or language issues (e.g. Bridgman et al., 2016 (web-cams), and Arnott et al., 2014 (group therapy)). Dr Bridgman also pointed out that co-morbidity wasn’t a predictor of Lidcombe Program treatment effects in those studies, which is both interesting and counter-intuitive. I’d like to thank Dr Bridgman for taking the time to read and comment on an earlier version of this article.

Image: https://tinyurl.com/y4huy49o

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.