1. A minor problem?

Many people think lisps are minor ‘first world problems’, like getting the wrong coffee at Starbucks or your iPhone earplugs getting tangled in your pocket. That attitude really gets me riled up.

Compared to disorders like severe apraxia of speech, specific language impairment or dyslexia, lisps can seem cosmetic – unless you or your child has one. Consider two examples:

- A 6 year old boy with a very minor lisp who is bullied mercilessly every day for an entire school term. He has to change schools to escape the taunts.

- An adult stroke patient with aphasia tears up when presented with a list of /s/ words to practice – the memories of his former colleagues paying him out for his lisp still haunt him, though he faces much bigger challenges re-learning to use language.

Of course, some adults aren’t troubled by their lisps in the slightest. I read about an entrepreneur who considered her lisp to be part of her ‘personal brand’!

When assessing lisps, it’s important to consider the severity of the problem. But it’s also essential to assess how (if at all) the lisp affects the person’s activities and participation in the real world (including school or work). In other words, does the lisp affect the client’s quality of life?

2. A potted history

The lisp is probably one of the most well-known – and widely mocked – kinds of speech disorder. The word has its roots in Old English, and there are historical accounts of people with lisps dating back thousands of years. Those who lisp include:

- historical figures such as Alcibiades;

- celebrities such as Ita Buttrose and Drew Barrymore; and

- characters like Sylvester the Cat, Grubby from dirtgirlworld and Pontius Pilate in Life of Brian.

Throughout history, people who lisp have been teased, taunted and humiliated – you just have to read Aristophanes’ thinly-veiled swipe at Alcibiades in The Wasps to understand that nothing is new under the sun when it comes to being teased for a lisp.

3. What is a lisp?

Unlike phonological problems, a lisp is a speech (not a language) problem. It is an inability to produce a specific speech sound or sounds correctly – most commonly /s/ and/or /z/.

Some speech-pathologists give a lisp technical-sounding names like ‘a sub-type of functional speech disorder’. For clarity, we prefer to call a lisp a lisp, unless the client has an aversion to the word, e.g. if a school-aged child has been labeled a ‘lisper’ by his peers.

4. What causes lisps?

Theories abound, though no-one knows for sure.

Speech is a learned skill that becomes increasingly automatic with practice – like driving a car or playing the piano. Many theorists talk about people who lisp learning or ‘overlearning’ the wrong patterns for their /s/ or /z/ sounds. There’s evidence that some children fail to learn the correct sound because they don’t hear themselves making errors. Sometimes the client has produced /s/ in that way for years and has never been corrected, until they are teased for it at school. Other times, the client may have received a lot of praise as a young child for sounding ‘cute’ and just kept doing it. Some children have problems with both articulation (speech) and phonology (language) that affect /s/ and /z/, making treatment especially tricky.

Though it seems like an odd thing to say, the research tells us we don’t need to know the cause of a particular lisp to fix it.

5. Are there different kinds of lisp?

Yes. The two most common types are the:

- interdental (i.e. between the teeth), which occurs when the tongue sticks out between the teeth making /s/ and /z/ sound like ‘th’; and

- lateral (i.e. sideways), where the tongue is in roughly the right place, but the air is directed over the sides of the tongue, rather than straight down the middle, creating a wet or ‘slushy’ /s/.

Other kinds of lisp include a palatal lisp, where the tongue touches the soft palate – way too far back in the mouth. But interdental and lateral lisps are by far the most common kinds we see in practice.

6. Do lisps fix themselves?

‘Sometimes.’ (Not a satisfying answer!)

Interdental lisps are quite common in children younger than 5, and, in most cases, resolve themselves with practice. Lateral lisps – which are not part of normal speech development – are far less likely to fix themselves.

As far as we know, not much research has been done so far on natural recovery rates, or identifying red flags to indicate when there might be a long-term problem.

7. When should you seek help?

Again, views vary, but research suggests that children are often bullied at school for speech impediments. We also know that lisping, like a bad habit, can become more and more entrenched with time. For interdental lisps, we recommend:

- parents seek advice from a speech-language pathologist at least six months before their child is due to start school – if possible before their 5th birthday; and

- adults who lisp be treated as soon as possible.

For lateral lisps, we recommend the client be referred to a speech pathologist for treatment as soon as possible.

8. How do speech pathologists treat lisps?

On the Internet, there is a wealth of great (and not-so-great) information, tips and tricks for treating lisps. Of the good stuff, I thoroughly recommend checking out Caroline Bowen’s information sheet and Heidi Hanks’ discussion of their methods and particular techniques, like the butterfly procedure and training /s/ from /t/. (The questions and comments on Heidi’s post will give you a good feel for how passionately people feel about lisps.)

Underpinning most mainstream intervention approaches, tips and tricks is what is known as ‘traditional articulation therapy’. Since the 1950s – and probably before that – speech-language pathologists have treated lisps using structured, step-by-step programs based on principles of behaviourism. In 1958, Charles Van Riper and John Irwin published ‘Voice and Articulation’, a book that still influences our approach today (I’ve read it a few times and still find helpful suggestions for clients).

Van Riper and Irwin were of the view that, in therapy, the client needs to learn to:

- scan the back-flow of sounds from his/her mouth – i.e. respond to feedback from his/her ears, mouth and tongue;

- compare the sounds coming from his/her mouth to the ‘standard’ or correct sound;

- correct/vary his/her production of the sound, to decrease the error;

- search for a precise combination of feeling and movement to produce auditory feedback for the sound that matches standard;

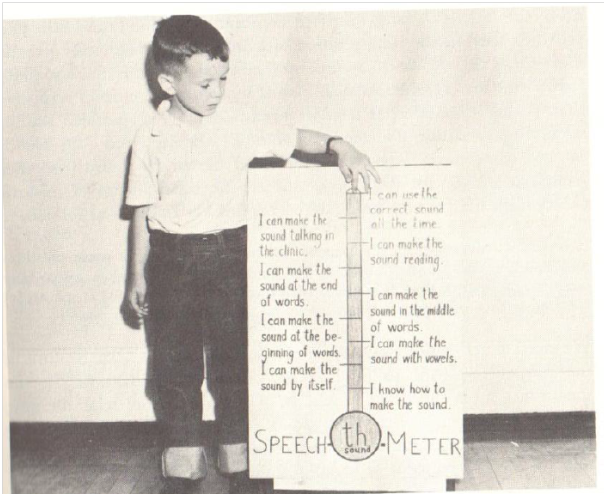

- fixate on the new sound: by strengthening and practising it repeatedly, at first in isolation, then in nonsense syllables based on the targets; then words with the sound at the end, middle and beginning, then sentences laden with the target sound, then structured and unstructured conversations; and

- stabilise the new sound by holding onto it under emotional stress like fear, excitement and time pressure.

More recently, speech-language pathologists have have started to incorporate the latest research on the principles of motor learning into articulation therapy. Based on studies of sportspeople and others learning a new skill (such as golf, playing a musical instrument or learning to speak), these principles have the potential to revolutionise the way speech pathologists tackle articulation and other speech problems. The most promising part of this research is that incorporating principles of motor learning may result in better ‘real world’ outcomes for clients.

We’ll be writing more about specific principles of motor learning – and how clients with speech disorders can benefit from therapy based on them – in a separate article. We’ve also developed a course for adults who would like to fix their lisps and another for older children with interdental lisps.

9. What to do if a fixed lisp won’t stay fixed

Though it can take lots of hard work and practice, lisps can often be corrected in the clinic and other controlled settings. The most difficult stage for many clients is using the correct sound consistently in the ‘real world’ – especially when excited, angry or stressed. This is the stabilisation stage of therapy referred to above (also known as generalisation or transfer stage).

The theory and practice of getting the correct sound to stick in the real world is a very big – and hugely important – topic. We’ll do our best to address it at length soon.

Related articles:

- Lisp Fixer Course for Adults

- The Pesky Lisp Fixer: a new evidence-based approach for kids whose interdental lisps won’t stay fixed!

- I’m an adult who lisps. Do I need speech therapy?

- How to use principles of motor learning to improve your speech

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.

Leave a Reply