Dear Son

Last year, I watched you sitting at your desk, studying hard for exams. I saw you tap furiously away at your school laptop, scroll through online textbooks, and cut and paste paragraphs of text into Google Docs. I saw you fighting the urge – valiantly – to tab out of what you were studying to surf the Internet or to play games.

You’ve got a good memory, and you’re a strong reader and writer. You did well. I’m proud of you.

But it’s time for some changes. As you head into Year 9 (Editor’s note: a Year 9 student is a Freshman for those of you in North America), it’s time to up your game. This year, I want you to learn to take notes; and I want you to learn how to review them properly. To help out, I’ve:

- spent some time reading peer-reviewed evidence on good note-taking practices; and

- summarised the main points below to explain why it’s important, and how to do it.

I’m not picking on you. In fact, to help others in the same boat, I’m sharing this letter with everyone.

Why note-making matters

Note-taking is a fundamental academic skill. It’s useful for tests, assignments, essays, and projects. More importantly, it’s useful for long-term learning of stuff you need to know as a young adult.

Over the years, you’ve probably seen me taking lots of notes as I go about my day. It’s not (just) because I’m sometimes forgetful. Evidence shows adults write more notes than young people because we have a better awareness of the need and value of note-taking. Way back in 2006, a researcher called Kobayashi looked at 33 note-taking studies and found that:

- the positive effects of note-taking and reviewing notes were substantial compared to not taking notes; and

- reviewing your notes substantially heightens the value of note-taking.

In 2012, Boyle and Rivera found that students who used note-taking techniques were effective at increasing scores of measures of achievement and the quality and quantity of notes recorded. In 2015, Chang and Ku reviewed previous studies and found that “note-taking instruction increases the level of free recall, scores on comprehension tests, enhances problem-solving, and helps students learn to include more relevant ideas”.

The problem is that note-taking and revision are hard to do well. Often, students have to learn to do them by trial and error, which wastes time and energy.

Here’s the good news.

Good note-taking can be taught (and learned)

It involves:

- reading the text;

- reducing or summarising the information in the text in your own words, focusing on main points;

- reorganising the information into a structure that’s easier to use, often with the aid of visuals and organisers;

- retrieving information from your memory, rather than just copying it down; and

- linking new information to things you already know (also known as “elaboration”).

Effective note-taking improves learning efficiency substantially, compared with more passive study techniques like simple reading.

10 steps to good note-taking

Here are some practical, evidence-based strategies and tips for taking good notes:

1: Prepare a space to take notes without interruption. Have a dedicated note-taking space away from screens and others. Put away your laptop and phone. The space does not need to be big. But, ideally, don’t share the space with anyone else while you’re working.

2: Establish notebooks or folders for each subject: For each school subject, have a dedicated notebook or folder filled with blank pages just for study notes. Assign each subject a different colour, e.g. red for maths, blue for music, green for science, etc., so you can sort your notes easily.

3: Schedule time for daily note-taking: Make a timetable for note-taking. This is in addition to day-to-day homework and assignment time. Dedicate at least an 1.5 hours every school day to making good notes for your subjects. Make notes for two different subjects each day, and change subjects every 45 minutes. Use timers to keep you on track. Do not study one subject for too long. Cycle through your subjects. Studying every day means that you won’t have to cram hard before exams. If you cycle between subjects and review your notes regularly, you are more likely to remember things for exams and for life. The technical words for these routines are distributed (spaced) practice and interleaving, and you can read about why they work here.

4: Use pens and paper: Pens and paper are cheap, fast, versatile and easy to use. They don’t need to be charged or updated. Handwriting your notes will encourage you to summarise information and to put it into your own words. It may also make your notes easier to remember when it comes time to study for exams.

5: When you sit down to study a text, think about the structure of what you are reading and why you are reading it. Understanding structures within a text can help you to find the main ideas, and to then organise them into notes. Look for three main types of structures within texts:

- main headings and subheadings – these can help generate outlines;

- sequences: these describe continuous and connected series of events (e.g. as in history) and steps in a process (e.g. as in science); and

- classifications: grouping things into classes and categories, often so you can later define, compare and contrast things.

6: If a teacher gives you notes, use them, but still make your own notes: Some teachers give you notes. By all means, use them to give you a framework for organising your notes. But don’t rely on your teacher’s notes alone. Depending on others’ notes might get in the way of you learning how to learn on your own. And you won’t remember someone else’s notes as well as your own come exam time.

7: Wherever possible, study using physical text books and printed materials. Read them, mark them up, rip out the main points and take notes using the Cornell note-taking system. Good note-taking is messy, active and creative. Text books are tools, and it’s OK to write in them – you have my blessing. Your aim is to mentally “rip out” the main points, and to jot them down in a way that helps get them into you brain. This is how to do it:

- Open your notebook next to the text you are reading, and grab pens and a highlighter.

- Flick through the text to see how long it is and to get an idea for its structure.

- Look for obvious signposts, like headings and sub-headings to get a rough idea of the topic – mind map the headings into your notebook so you have a basic idea of the text’s content and structure.

- Highlight the main ideas – in well-written texts, the main ideas are often in the first sentence of each paragraph and in the first and last couple paragraphs of a text. Mark important ideas, information and words you don’t know by underlining or circling them. When you come across a really important point (often at the end of a section), add some asterisks (*). Scribble any initial thoughts or questions you may have in the margins.

- Have a 5-10 minute break. Have a snack (save some Honey Jumbles for me). Take a short walk.

- Come back to the desk, and write the main points in your notebook. I recommend watching this short video on the Cornell note-taking method (e.g. Pauk & Ross, 2010) and then using the method to take notes. Your notes (including any visuals) go in the main note-taking column on the right. Keywords, new vocabulary, comments, and questions go in the smaller column on the left. Use your own words. (It’s really important not to just copy slabs of text.) Write down what you learned as if you are explaining it to someone. Ask yourself questions as you do it.

8: Crunch them down. As you progress at school, you need to get quicker at note-taking. Your notes can’t be too long:

- Find the main points and write them down in short, simple sentences.

- Get rid of unnecessary words (like “the”, “for”, “in”, etc.).

- Replace long lists with the category, e.g. instead of “horses, cows, sheep, goats, ducks, and geese”, write “farm animals”; instead of “the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Portugal” write “Western Europe”.

- Use symbols and abbreviations. For example, I use the symbol “~” to refer to the topic I’m studying, e.g. If I’m studying igneous rocks, I use “~” to mean “igneous rocks”. I use “b/c” for because, and “w/” for with, “+” for positive/pros, “-” for negative/cons, and “=” for equals or equivalent to. I use

↑ for increase, and

↓ for decrease. I use arrows to show cause/effect relationships.

9: Look for keywords to help you find connections between the ideas you are studying: If you are:

- comparing two ideas, look for “however”, but”, “although” and “while”;

- learning about a cause/effect relationship, look for “because”, “so” and “as a result” and “therefore”; and

- learning about a sequence or process, look for “first”, “second/next”, “third” and “final”.

You can then summarise the relationships with numbers and arrows, or use mnemonics. For example:

- Food chain: energy from sun → plants → herbivores → carnivore (or omnivore).

- Rock classes: 1. magma; 2. igneous; 3. sedimentary 4. metamorphic.

- Earth layers, top to bottom: continental crust, oceanic crust, mantle, outer core, inner core.

- Common elements on earth (by %, not weight): 1. Oxygen 2. Iron 3. Silicon 4. Magnesium 5. Sulphur.

- Causes of WWI: Militarism, Alliances, Nationalism, Imperialism and Assassination (MANIA → WWI).

- Visible colour spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet (Colours = ROY G. BIV).

10: Use visuals to reorganise information to make things easier to remember and to link it to what you already know: Use pictures, graphs, charts, diagrams to show the structure and relationships between concepts. For example, use:

- mind mapping (radially mapping ideas around a central idea) to make an overview of a text’s structure (table of contents, headings, topic sentences, conclusions) and existing knowledge on topic. For an overview, check out this Tedx Talk on Mind Mapping by Hazel Wagner; and

- tables to compare two or more things by different features, or to list similarities and differences. Here’s a simple example comparing a Venus fly trap to a death cap mushroom:

| Same | Different |

| Alive | Type of living thing: plant v fungus |

| Grow | Seeds (for Venus flytrap) spores (for death cap mushroom) |

| Made of cells | Venus flytrap digests insects and spiders |

| Both evolved from single celled “protists” | Death cap mushroom is poisonous to humans |

- Venn diagrams to show similarities and differences between two or more things;

- a flowchart to show a sequence of steps or a cycle diagram to demonstrate a cyclical relationship;

- a story map to summarise a narrative;

- an expository text organiser to summarise an expository text. For example, check out this simple one from the Florida Reading Center;

- charts to illustrate key relationships between two variables;

- tree diagrams for hierarchies and for showing categories and subcategories;

- a timeline to help map significant events over time; and

- blue prints for designs and construction tasks.

So let’s get started

This all might seem like a lot of work. It will be to start with. But once you know how to do it properly, and get into a routine, these note-taking skills will help you with high school, university and hopefully, one day, paid work!

It’s a new year, and we both have so many opportunities to learn about the world around us.

Don’t roll your eyes at me, young man!

Love Dad

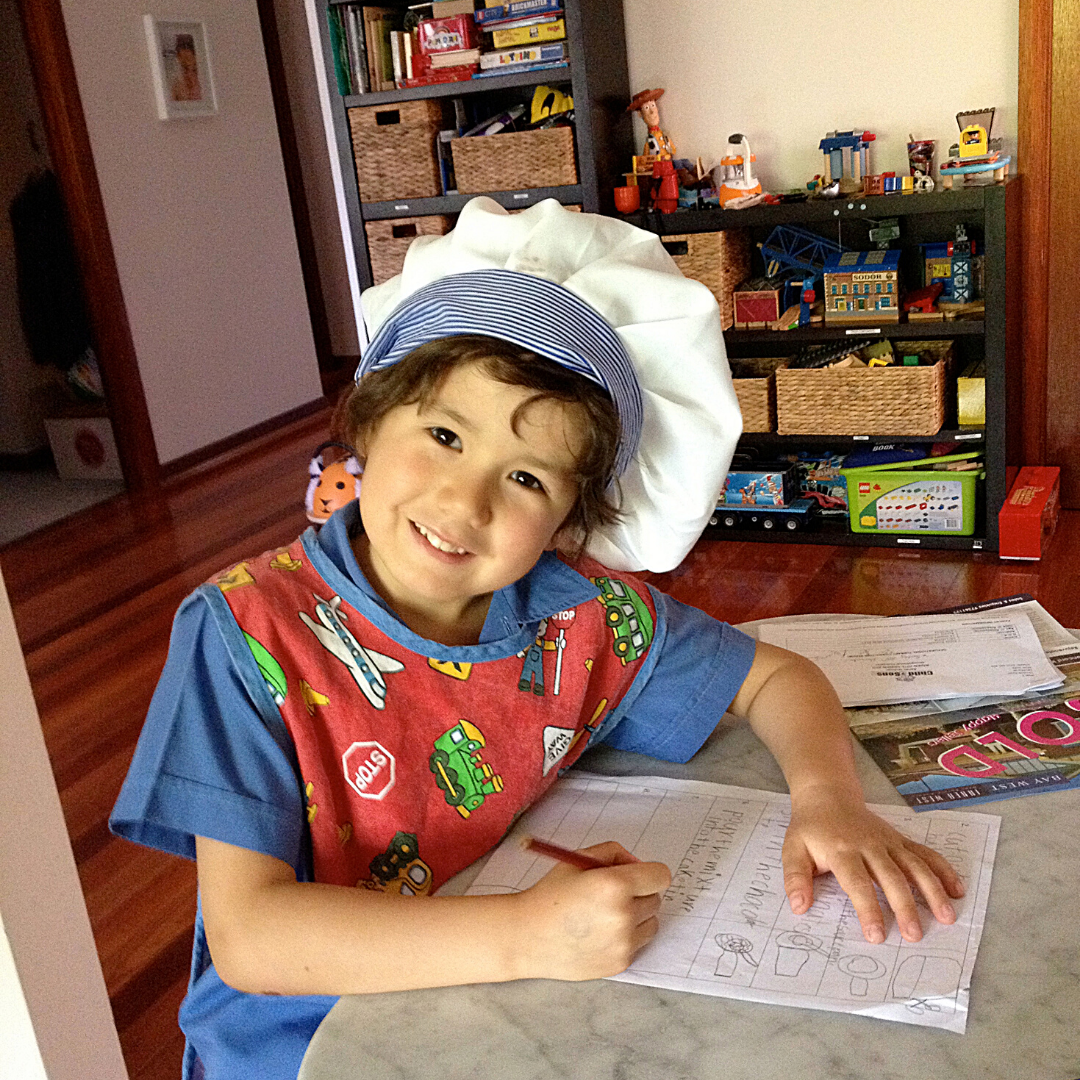

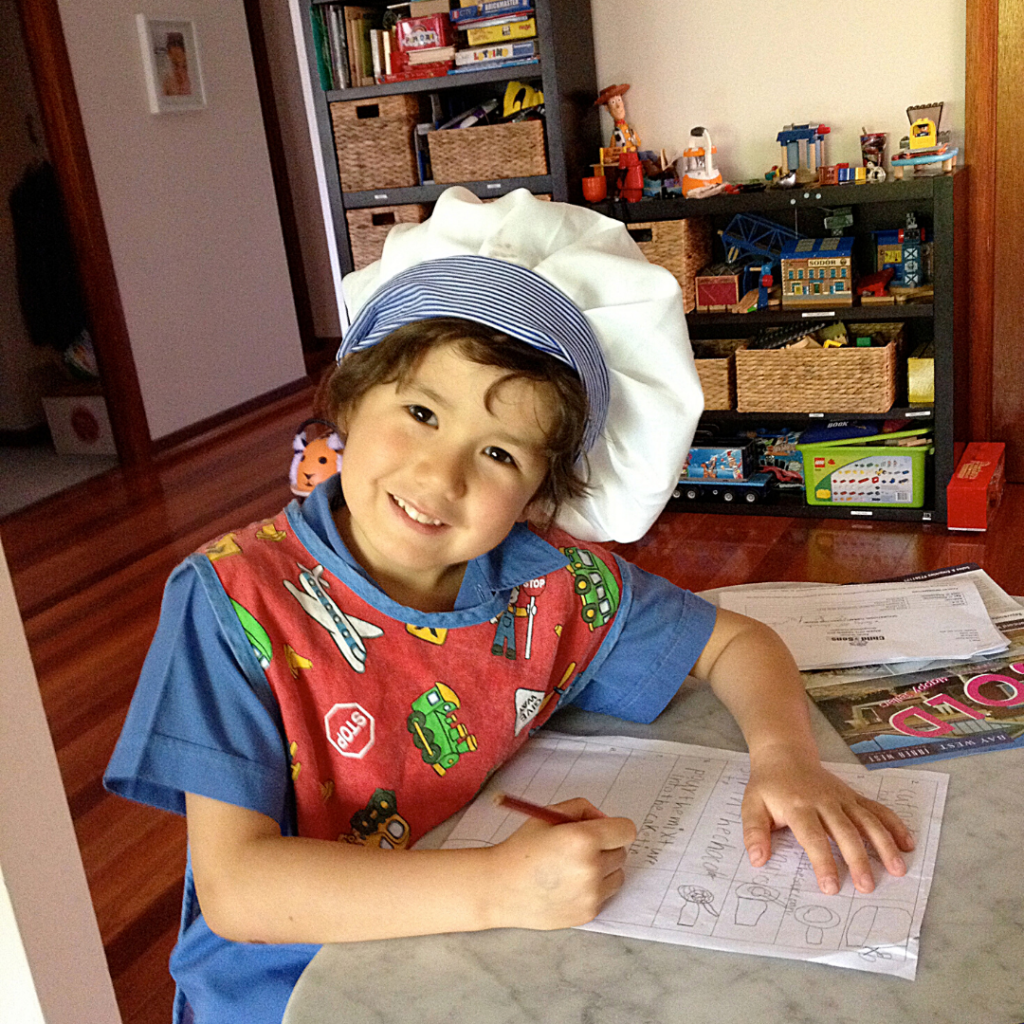

PS. Here’s a photo of you writing recipe notes in Kindergarten.

Principal sources:

- Kobayashi, K. (2006). Combined Effects of Note-Taking/Reviewing on Learning and the Enhancement through Interventions: A meta-analytic review, Educational Psychology, 26(3), 459-477.

- Boyle, J.R., & Rivera, T.Z. (2012). Note-Taking Techniques for Students With Disabilities: A Systematic Review of the Research, Learning Disability Quarterly, 35(3), 131-143.

- Chang, WC. & Ku, YM. (2015). The Effects of Note-Taking Skills Instruction on Elementary Students’ Reading. Journal of Education Research, 108: 278-291.

- Ukrainetz, T.A. (2020). Sketch and Speak: An Expository Intervention Using Note-Taking and Oral Practice for Children With Language-Related Learning Disabilities, Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 50, 53-70.

Related articles:

- How to improve exam results: 9 free evidence-based DIY strategies

- Back-to-school study skill: 3 steps to remember any 10 things in order

- Want better school results? Avoid the hype and use free, evidence-based learning strategies

- Worried about the HSC? 8 practical (and free) things you can do this week to get ready

- Starting high school? 6 practical, evidence-based principles to help students succeed at STEM subjects

- Want your writing to sound smarter? Get rid of pointless, long words!

- Apologies to Mrs Dixon: taking notes by hand is more effective than by laptop

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.